Denial Is Certainly More Than a River in....So Say The Psychologists

The New York Times has a thought-provoking article today by Benedict Carey on the role of denial in the daily social lives of ordinary people. So much more than the relatively primitive defense mechanism described by Freud and his adherents, denial appears to be central to the ways in which our social lives are rendered tolerable. The crucial summary in Carey's article notes

I could not help but be struck by the way in which this article suggests in preliminary fashion an understanding of how scandals may arise among those in positions of authority or by those who "should have known better." I am thinking both about what goes on in the political world as well as the religious one as well. The doleful news that the Jesuits in the Oregon Province have just agreed to a $50 million settlement for the abuse that went on in the Alaskan mission during the past forty or so years is haunting. The painful reality that the victims experienced seems so obvious now that a final explanation of malice and sheer injustice by Jesuit superiors seems almost inescapable. But, if the work cited by Carey here among social psychologists is accurate, then a more nuanced understanding may eventually begin to emerge to explain the failure of the Church and its superiors in this horrendous scandal. Toward the end of his report, Carey summarizes: "In short, social mores often work to shrink the space in which a conspiracy of silence can be broken: not at work, not out here in public, not around the dinner table, not here. It takes an outside crisis to break the denial, and no one needs a psychological study to know how that ends." This seems like something that we'll need to think about very hard in the years ahead.Yet recent studies from fields as diverse as psychology and anthropology suggest that the ability to look the other way, while potentially destructive, is also critically important to forming and nourishing close relationships. The psychological tricks that people use to ignore a festering problem in their own households are the same ones that they need to live with everyday human dishonesty and betrayal, their own and others’. And it is these highly evolved abilities, research suggests, that provide the foundation for that most disarming of all human invitations, forgiveness. In this emerging view, social scientists see denial on a broader spectrum — from benign inattention to passive acknowledgment to full-blown, willful blindness — on the part of couples, social groups and organizations, as well as individuals. Seeing denial in this way, some scientists argue, helps clarify when it is wise to manage a difficult person or personal situation, and when it threatens to become a kind of infectious silent trance that can make hypocrites of otherwise forthright people.

Reference

Carey, B. (2007, November 20). Denial makes the world go round (Electronic version). New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/20/health/research/20deni.html?ex=1353301200&en=d185b9c072a51a1f&ei=5124&partner=permalink&exprod=permalinkThe Internet and Children: What's the Impact?

- "It's Fun, but Does It Make You Smarter?" (Internet use and academic performance)

- "Socially Wired" (Instant messaging & email; friendships; how much is too much?)

- "Web Pornography's Effects on Children" (Development of unhealthy attitudes toward sex)

- "Creating a Place for MySpace" (Advice for parents)

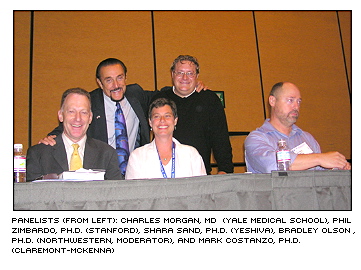

APA San Francisco (Fri): The Question of Torture

The pressing issue of this convention turns out to be the question of the torture of prisoners by the United States government's forces in places like Guantanamo Bay, the involvement of psychologists in developing or advising about interrogation techniques which are torturous, and the ethical lapses or failures of both these psychologists and the American Psychological Association itself in rejecting such activities. My first session this morning involved a symposium/discussion on the topic: "Ethics and Interrogations-Confronting the Challenge: What Does the Research on

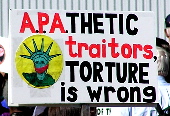

Later in the day, there was a demonstration in the Yerba Buena Gardens across from Moscone South by Psychologists for an Ethical APA. The crowd it attracted seemed to me to consist of about 200-300 pretty committed and enthusiastic. On Sunday morning, the APA Council of Representatives is going

Eyewitness Testimony Again Challenged

The articles goes on to say thatBrandon L. Garrett, a law professor at the University of Virginia, has, for the first time, systematically examined the 200 cases, in which innocent people served an average of 12 years in prison. In each case, of course, the evidence used to convict them was at least flawed and often false — yet juries, trial judges and appellate courts failed to notice.“A few types of unreliable trial evidence predictably supported wrongful convictions,” Professor Garrett concluded in his study, “Judging Innocence,” to be published in The Columbia Law Review in January.

Once again, naive belief in the accuracy or superiority of so-called "eyewitness" testimony is shown to be dangerous and grossly misplaced.The leading cause of the wrongful convictions was erroneous identification by eyewitnesses, which occurred 79 percent of the time. In a quarter of the cases, such testimony was the only direct evidence against the defendant.

Target Article: Liptak, A. (2007, July 23). Study of wrongful convictions raises questions beyond DNA. New York Times (Electronic version).