Hooking Teens on Cigarettes in a Flash

In a new clinical study reported in the July, 2007 issue of the Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, the researchers followed 1246 sixth-grade students in Massachusetts for four years. By the end of their study, 217 of their participants reported inhaling while smoking. So, how many of these 10th graders could now be considered dependent on nicotine? Using the "Hooked on Nicotine Checklist" as the measure of loss of autonomy over tobacco and the ICD-10's definition of tobacco dependence, the results were startling. More than half these adolescents (N = 127; 54.5% of smokers) had lost their autonomy over tobacco use and 83 inhalers (38.2% of smokers) were fully tobacco dependent. Further, the speed with which autonomy loss was reached was extremely fast: 10% of these smokers had lost their autonomy within 2 days of beginning to smoke and 25% within the first month of first inhaling. Of those who were tobacco dependent, half had reached that condition by the time they were smoking just 46 cigarettes per month, i.e., one and a half cigarettes per day. The authors conclude

These data ought to speak loud and clear (though I know they won't) to teenagers and young adults who think that a couple of cigarettes every once in a while mean nothing. The ease with which tobacco use hooks its addicts is simply amazing.[t]he most susceptible youths lose autonomy over tobacco within a day or 2 of first inhaling from a cigarette. The appearance of tobacco withdrawal symptoms and failed attempts at cessation can precede daily smoking; ICD-10-defined dependence can precede daily smoking and typically appears before consumption reaches 2 cigarettes per day.

Target article: DiFranza, J. R., Savageau, J. A., Fletcher, K., O'Loughlin, J., Pbert, L., Ockene, J. K., McNeill, A. D., Hazelton, J., Friedman, K., Dussault, G., Wood, C, & Wellman, R. J. (2007). Symptoms of tobacco dependence after brief intermittent use: The development and assessment of nicotine dependence in Youth-2 study. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 161, 704-710. [Link to abstract]

Newspaper report: Bakalar, N. (2007, July 31). Nicotine addiction is quick in youths, research finds. New York Times [Electronic version]

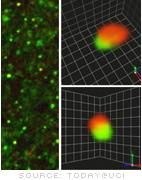

The image above is Copyright © Wellcome Images, but has been altered into a Derivative Work by the author by a colorization change.

Searching for the "Engram" and Finding It at UC-Irvine

Following upon the work of Ramon y Cajal and Sherrington, the Canadian neuropsychologist, Donald O. Hebb (1904-1985), disagreed with Lashley and argued for a mechanism by which memories could be localized, i.e., his proposal for the "Hebbian synapse" on the neuron and collections of such synapses across associated neurons in the form of "cell assemblies" (see Brown & Milner, 2003, for a longer appreciation of Hebb's contributions). For the past four decades, the focus for identifying Hebbian synapses has been undertaken under the overarching research concern for long-term potentiation (LPT), that is, the assumption that "information is storied in the brain as changes in synaptic efficiency..." and that "the location of storage, the engram of learning and memory, must therefore be found among those synapses which support activity-dependent changes in synaptic efficiency" (Bliss & Collingridge, 1993, p. 31).

So, more than a century after Semon proposed a role for a physical trace in the brain's cell in the establishment of a memory, laboratory research has appeared to confirm this finding.the study shows that synaptic connections in a region of rats' brains critical to learning change shape when the rodents learn to navigate a new, complex environment. In turn, when drugs are administered that block these changes, the rats don’t learn, confirming the essential role the shape change plays in the production of stable memory...Working with advanced microscopic techniques called restorative deconvolution microscopy, the UC Irvine team found that the LTP-related markers appear during learning and are associated with expanded synapses in the hippocampus. Because the size of a synapse relates to its effectiveness in transmitting messages between neurons, the new results indicate that learning improves communication between particular groups of brain cells. (UC Irvine scientists, 2007, July 25).

Target article: Fedulov, V., Rex, C. S., Simmons, D. A., Palmer, L., Gall, C. M., & Lynch, G. (2007). Evidence that long-term potentiation occurs within individual hippocampal synapses during learning. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(30), 8031-8039. [Link to abstract]

Press release: UC Irvine scientists unveil the 'face' of a new memory [Press release]. (2007, July 24). Today@UCI. Retrieved July 31, 2007 from the UCI website: http://today.uci.edu/news/release_detail.asp?key=1638

References

Bliss, T. V. P., & Collingridge, G. L. (1993, Jan 7). A synaptic model of memory: Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature, 361(6407), 31-39.

Brown, R. E., & Milner, P. M. (2003). The legacy of Donald O. Hebb: More than the Hebb synapse. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4, 1013-1019. Retrieved July 31, 2007 from http://www.nature.com/nrn/journal/v4/n12/full/nrn1257_fs.html

Cherkin, A. (1966, Jan 15). Toward a quantitative view of the engram. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 55(1), 89-91.

Hebb, D. O. (1949). The organization of behavior: A neuropsychological theory. New York: Wiley. (Reprinted by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002.)

Semon, R. (1904). Die Mneme als erhaltendes Prinzip im Wechsel des organischen Geschehens. Leipzig, Germany: Wilhelm Engelmann.

Semon, R. (1921). The mneme. London: Allen and Unwin.

Wellcome Trust Opens Image Collection Online

Cannabis & Later Psychosis: The Lancet Meta-analysis

A new meta-analysis published in British medical journal, The Lancet, argues that the use of cannabis is not at all an innocent pleasure. Rather, in a review of the combined results of 35 population-based longitudinal observational studies of the relationship between the use of cannabis and psychiatric disorders in later life, the authors found an overall increased risk of 41% in the development of any psychosis among individuals who had used marijuana in the past. The summary of their findings reports:

These results were so persuasive that the editors of The Lancet editorialized as follows:There was an increased risk of any psychotic outcome in individuals who had ever used cannabis (pooled adjusted odds ratio=1·41, 95% CI 1·20–1·65). Findings were consistent with a dose-response eff ect, with greater risk in people who used cannabis most frequently (2·09, 1·54–2·84). Results of analyses restricted to studies of more clinically relevant psychotic disorders were similar. Depression, suicidal thoughts, and anxiety outcomes were examined separately. Findings for these outcomes were less consistent, and fewer attempts were made to address non-causal explanations, than for psychosis. A substantial confounding effect was present for both psychotic and affective outcomes.

So, has the question been settled? Is it clear that marijuana is a dangerous drug which can cause irreparable harm to its users? It would be stretching the scientific arguments advanced by Moore and her colleagues (2007) to use this study's findings as having settled this question in a definitive way. My reactions to this article include these thoughts:In 1995, we began a Lancet editorial with the since much-quoted words: “The smoking of cannabis, even long term, is not harmful to health.” Research published since 1995, including Moore's systematic review in this issue, leads us now to conclude that cannabis use could increase the risk of psychotic illness. ("Rehashing the evidence...," 2007)

- It is likely that using marijuana increases the risk of psychotic illness in later life for some small percentage of the population. And, since psychotic illness can be quite debilitating and tends to follow a chronic course, the danger may be substantial that some marijuana users are putting their later life in real jeopardy.

- Correlation, as our basic research theories tell us, can never prove causation. All of the studies examined by Moore et al. (2007) were correlational in nature. Further, the additional use of meta-analytic grouping techniques cannot turn correlational data into experimental data no matter how sophisticated the statistics. This means that, while the trends and the thrust of the data seems to make marijuana a very promising explanatory causal factor in the development of some of the psychoses that these research participants developed, such a link has not been conclusively demonstrated. And, while the gross odds ratio speaks of a 41% increased risk, the authors themselves acknowledge the impact of confounding and other variables in lowering the risk percentage in the studies they examined. Hence, we are left without a good estimate of what the actual increased risk might be.

- This last point is related to a fundamental set of questions about causality in the area of drug risk research. The primary question concerns how much the decision to use marijuana (in earlier life) and the development of a psychotic illness (in later life) might BOTH be causally related to an underlying third factor. Might it be possible that there is a genetic determinant or a genetic x environmental interactive determinant that could explain a large proportion of the relationship identified in this study? Alternatively, since we know that psychosis tends to emerge in adulthood rather than adolescence, might it be possible that pre-psychotic adolescents might be "self-medicating" or using marijuana to ward off their sense of an increasingly unstable or deteriorating psychological state and this would then serve to explain the sequence of drug use preceeding the appearance of tangible psychotic symptoms? Such questions demand further study.

Press release: Cannabis could increase risk of psychotic illness in later life by over 40 percent [Press release]. (2007, July 26). EurekAlert!.

References

Nordentoft, M., & Hjorthøj, C. (2007, July 28-August 3). Cannabis use and risk of psychosis later in life. The Lancet, 370, 293-294. (Commentary)

Rehashing the evidence on psychosis and cannabis [Editorial]. (2007, July 28-August 3). The Lancet, 370, 292.

====================

Update 7/30/07 11:30 pm

A respondent to Andrew Sullivan's excellent blog has posted a detailed argument why cannabis is not congenial to the mental health of many of its users. I found the posting persuasive and have posted a link to it here.

Albert Ellis Dies at 93

Target article: Kaufman, M. T. (2007, July 25). Albert Ellis, influential psychotherapist, dies at 93. New York Times. Retrieved July 24, 2007 from the New York Times website.

Resources: Albert Ellis Institute | Albert Ellis (@ Wikipedia)

Tiny Brain Normal Life

![[MRI image of hydrocephalus]](page0_blog_entry2_1.jpg)

(Image taken from Wired Science blog)

The interior of the man's brain consisted mostly of fluid-filled ventricles with highly compressed brain tissue. Somehow, as the man grew up and the brain structure grew increasingly small, the brain was able to compensate. The man's IQ level was in the borderline range (full IQ = 75; verbal IQ = 84; performance IQ = 70), but permitted him to marry, father two children, and maintain a job as a government worker. (Read more at ScienceDirect).

Target article: Feuillet, L., Dufour, H., & Pelletier, J. (2007, July 21). Brain of a white-coloar worker. The Lancet, 370, 262.

Eyewitness Testimony Again Challenged

The articles goes on to say thatBrandon L. Garrett, a law professor at the University of Virginia, has, for the first time, systematically examined the 200 cases, in which innocent people served an average of 12 years in prison. In each case, of course, the evidence used to convict them was at least flawed and often false — yet juries, trial judges and appellate courts failed to notice.“A few types of unreliable trial evidence predictably supported wrongful convictions,” Professor Garrett concluded in his study, “Judging Innocence,” to be published in The Columbia Law Review in January.

Once again, naive belief in the accuracy or superiority of so-called "eyewitness" testimony is shown to be dangerous and grossly misplaced.The leading cause of the wrongful convictions was erroneous identification by eyewitnesses, which occurred 79 percent of the time. In a quarter of the cases, such testimony was the only direct evidence against the defendant.

Target Article: Liptak, A. (2007, July 23). Study of wrongful convictions raises questions beyond DNA. New York Times (Electronic version).

Beginning This Blog

I am beginning this blog, Storied Conduct, anew as a place to highlight news and recent information in the fields of psychology and the allied social and natural sciences. I recently got RapidWeaver software to help me compose materials for online publishing. So, I am hoping that I can begin to use this blog as a mechanism to share with my classes and anyone else coming here what I have found to be intriguing or exciting in the areas I teach and read.