Sept. 19, 2023

PSY 444

Story in Psychology: Narrative Perspectives on Human

Behavior

|

Sept. 19, 2023 |

PSY 444

Story in Psychology: Narrative Perspectives on Human

Behavior |

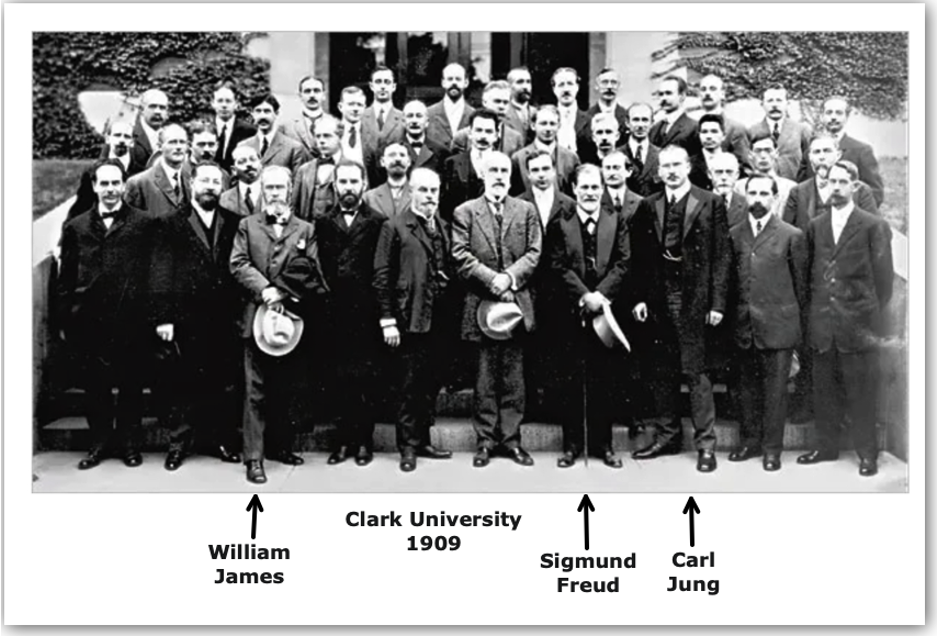

Clark University, Worcester, MA • September 10, 1909 • 20th Anniversary

- 42 world-renowned scholars gathered by G. Stanley Hall, President of Clark & psychologist.

- William James (founder of American psychology), Sigmund Freud, and Carl Jung were there. Each scholar gave a lecture.

- Freud was 53 and James 67-years-old. Already weakened physically and burdened by significant psychological distress in 1909, James died the following year of heart disease. With James in attendance, Freud described for his audience his theory of dreams. The two also shared a private discussion and a short stroll that had to be cut short by James who may have been experiencing an angina attack.

- While he publicly encouraged Freud, more privately James judged the founder of psychoanalysis "a man obsessed by fixed ideas"

Background and Education

William James (1842-1910)

- Grandson of William James, Sr., Irish immigrant and at his death one of the richest men in New York State. Along with Moses DeWitt, his grandfather is one of the founders of the city of Syracuse.

- James' father, Henry, sued to overturn his own father's will from which he was excluded, was successful in his suit, and the family thereafter enjoyed a great deal of wealth.

- The family traveled across the US and Europe throughout James' childhood and adolescence. His elementary/secondary education came mostly through tutors and self-learning.

- He was drawn to both working as an artist and studying science (medicine and physiology).

- He studied as an undergraduate at Harvard and, in 1864, entered the Harvard Medical School where he earned an M.D. degree (he never actually practiced as a doctor).

Professional Career

- Began to teach comparative physiology at Harvard in 1872.

- Established a laboratory and began teaching psychology in 1873-1874.

- Spent 1880 to 1890 writing his famous Principles of Psychology (1890, 2 volumes) and, then a condensed version, Psychology: Briefer Course. These books are still considered to be among the most insightful and engaging texts in the field: filled with ideas and provocative speculation.

- Near the end of the 19th century, James turned from psychology to teaching philosophy. He is one of the founders of the school of pragmatism

- “Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that views language and thought as tools for prediction, problem solving, and action, rather than describing, representing, or mirroring reality. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics—such as the nature of knowledge, language, concepts, meaning, belief, and science—are all best viewed in terms of their practical uses and successes.”{W}

- After a trip to Europe to care for his health, James returned to the United States where he died of heart disease on August 26, 1910, age 68, at the family vacation home in Chocorua, New Hampshire. See below the home itself and the room in which he died as they appeared in 2010.

James' Influence on Narrative Psychology

Why does James stand as a central figure for the narrative perspective in psychology? I suggest that James advanced two primary concepts that contribute even today to the ways that narrativists think. The first notion concerns his understanding of the nature of thinking and consciousness and the second involves his vision of the self as a plural reality.

A. The Nature of Thinking & Consciousness

James proposed that we all experience what is called the "stream of consciousness". In his Principles, he argued for five characteristics of human thinking:

(1) "Every thought tends to be part of a personal consciousness"

(2) "Within each personal consciousness thought is always changing"

(3) "Within each personal consciousness thought is sensibly contiguous" [i.e., no gaps between thoughts]

(4) "It always appears to deal with objects independent of itself"; and

(5) "It is interested in some parts of these objects to the exclusion of others, and welcomes or rejects – chooses from among them, in a word – all the while" (p. 225; italics added).

Rather than functioning in a passive way, that is, only reacting to what happens to it, the human mind is both complex and active. The human mind is constantly choosing to paying attention to and focus on many different aspects of reality in a continuous dynamic process. In various ways, James' understanding of the mind's way of functioning anticipates later constructivist models: based upon our individual experiences, we actively build or construct our knowledge and understanding of the world. Thus, while we share many ideas in common, there is a unique constellation of thoughts and experiences upon which we each live in the world.

B. The Self as a Plural Reality

1. The Self: "I" vs. "Me"

In one direction, James divided the self into two aspects: the "I" and the "Me". The "I" is the self as knower, a unified subjective or personal center of thinking whereas "Me" stands for the self as known (what James terms the "Empirical Self”). Here's how James explains the whole self:

In its widest possible sense, however, a man's Self is the sum total of all that he CAN call his, not only his body and his psychic powers, but his clothes and his house, his wife and children, his ancestors and friends, his reputation and works, his lands and horses, and yacht and bank-account" (p. 291, emphasis in the original)

So, what happens when we try to explain ourselves, that is, answer the question “who are you?” The “I” casts the self as an empirical object of investigation and exploration. That same empirical self might be constituted in different ways depending upon the story told while the knowing I maintains a primal sense of continuity and unity across time. At different times, we may tell different stories and our “empirical self” would appear to change.

2. The Plural Aspects of the Self

In another direction, James ultimately defines the plural constituents of the self as fourfold:

- First, the material Self, that is, our bodies as well as our clothes, families, and all the other objects or property which falls within our ownership, control, or influence.

- Secondly, the social Self which James defines as "the recognition which [we] get from [our] mates.... Properly speaking, a man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and carry and image of him in their mind." (pp. 293-4).

- Thirdly, the spiritual Self that he defines as our "inner or subjective being, psychic facilities or dispositions, taken concretely" (p. 296) [spiritual here does not mean religious as much as it points to cognitive activity] and,

- Finally, pure "Ego" (or the "I") that constitutes the "inner principle of personal unity" in the self. (p. 342)

This understanding of the self challenges the long tradition in Western culture which equates the self in terms of a spirit or immaterial presence that possesses its own unity and distinctiveness from all other realities.

The details of daily life in the concrete reality of homes, schools, cars, jobs, investments, tools of work, and their like are crucial to a full understand of a person as an individual. Further, the social self of James contains at its heart an awareness of the protean (multiple) ways in which human beings present themselves and are experienced by others. How I act in one situation may be very different than my behavior in another. Some of my colleagues and family may see me in one light while others might report on someone who appears quite different to them.

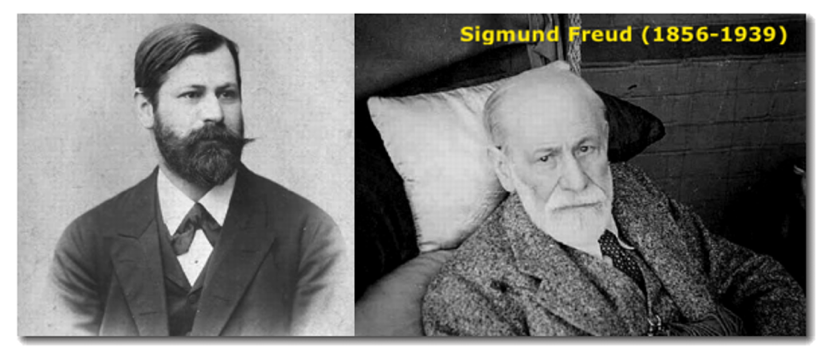

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)

The neurologist, Sigmund Freud, developed psychoanalysis as a complete theory of the human mind and personality in the late 19th and first part of the 20th century. It would be difficult to underestimate the impact or influence of psychoanalytic thought on the culture of the Western world through much of the 20th century. Whether in treating individuals with mental illness, in writing novels, plays, or films about individual persons and family, in advertising and selling products to consumers, or in how we raise and educate children and adolescents, Freud's notions were quite widely embraced in the 20th century.

Background and Education

An Austrian physician trained in neurology and neuropathology in addition to his position as the founder of psychoanalysis, Freud was born into a middle-class Jewish family in Moravia on May 6, 1856. The family moved to the capital city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Vienna, when Freud was 4-years-old. He was educated in the gymnasium and entered the University of Vienna as a medical student in 1873. There he worked at Ernst Brücke's Physiological Institute as a research scientist even after receiving his medical degree in 1881.

He was deeply impressed by his experience in the psychiatry service (of the Vienna General Hospital) headed by Theodore Meynert, an internationally recognized brain physiologist. Appointed a Privatdozent (Instructor) in neuropathology in 1885, Freud spent six months at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris with neurologist, Jean Martin Charcot. He returned to Vienna in 1886, set up his own practice as a neurologist, and married his fiancée, Martha Bernays.

Career & Professional Activity

From 1886 to 1900, Freud became increasingly involved in the treatment of patients showing symptoms of hysteria (bodily disturbances such as paralysis or sensory loss without any identifiable physical cause). His past discussions with Dr. Josef Breuer over the case of Anna O. (her real name = Bertha Pappenheim), extensive conversations and correspondence with his controversial friend, the ear-nose-throat specialist, Dr. Wilhelm Fleiss, and his own attempts to understand himself through a self-analysis brought Freud eventually to publish The Interpretation of Dreams in 1899/1900.

From 1900 until the end of the First World War, Freud fostered psychoanalysis as a new science and, through extensive writing and lecturing, gradually secured both recognition for his work and a cadre of disciples who shared his psychological vision. As noted above, he made is only trip to the United States in 1909 to lecture and receive an honorary degree at Clark University, an event he believed demonstrated the dawning acceptance of his theories.

During the last two decades of his life in the aftermath of the First World War, Freud found himself reformulating his basic understanding of the human mind (adding the functional model of id-ego-superego to the original structural systems model of the Cs [Conscious], Pcs [Preconscious], and Ucs [Unconscious]. His psychoanalytic practice brought many new patients to the consultation room of Berggasse 19 in Vienna.

Freud had to cope with recurrent cancer of the jaw beginning in 1923 and strongly pessimistic doubts regarding the ability of society ultimately to manage forces of irrationality and violence in common life. With the Nazi invasion of Austria in 1938, Freud's personal safety and that of his family became precarious. He was able to leave his homeland to settle in London later that year. He died on September 23, 1939 in pain and exile but celebrated internationally.

Freud's Influence on Narrative Psychology

Let me suggest that there are at least five important ways in which Freud's thought has had influence on the narrative perspective in psychology.

(1) Language and other behaviors are symbolic, determined, and require interpretation

Throughout Freud's writings, he asserts that the determinism which underlies any human action (and therefore the action's meaning) can be discovered by psychoanalytic techniques of free association and other interpretive procedures. For Freud, everything that humans do – dreams, thoughts, spoken language, and actions in the world – are filled with symbolic meanings. And, these can be recovered via diverse hermeneutic (interpretive) principles that placed a heavy reliance upon tropes (figures of speech), such as metaphor (one thing is like another: our love is like a rich meadow filled with beautiful flowers), metonymy (one thing stands for another: Pentagon = Department of Defense), synecdoche (one part stands for the whole: all hands on deck = all sailors on the ship), and others.

Freud speaks of includes not only simple attempts to link single associations one with the other. Rather, he offers extended and complex interpretations involving multiple layers of meaning and intentionality. His theory of condensation and displacement in dreams – where the simple structure or elements of a particular reverie serve metaphorically or in place of multiple associative memories and wishes – underscores the plurality of meaning he believed always inhered in human activity.

(2) Case study as a method of investigation

He employed detailed and compelling case histories in support of his theories. Hence, we have the stories of Anna O., Dora, Little Hans, the Rat Man, the Wolf Man, and others. While there are serious questions about the accuracy of what Freud recounts in some of these studies, there is little denying that his use of this format lent a persuasive lifelikeness prima facie to his theories and their practical applications.

(3) Development as Storied: The Oedipal Drama of Childhood

Freud’s extensive knowledge of literature in both the classical and modern eras gave him tools by which to understand psychic phenomena considering literature and myth. Probably the most famous ways in which he applied myth within psychoanalysis was his use of the ancient Greek story of Oedipus the King recounted so powerfully in the tragedy-drama of Sophocles Oedipus Tyrannus [Oedipus the King]. In Freud’s hands, the myth becomes a metaphorical guide to the ways in which young males develop within a family more generally. This is known as the Oedipal Complex.

(4) Time and the Unconscious

Freud's theory of primary process and its functioning within the id problematized time and sequence in human storytelling abilities. Processes of psychological defense and distortion could transpose events in time or create non-linear symbolic associations in events and experience. In recounting what has happened in the past, we may not remember correctly and what is the result of something might be seen as the cause. For example, a patient may tell their therapist that, when they were in elementary school, one of their parents became unreasonably angry and abusive. The patient might recall that the parent physically hit them and, in doing so, actually knocked them against a lamp which fell over and was broken. In reality, it might have been that the patient as a child was having a tantrum and knocked over the lamp in anger and the parent's physical hitting afterwards was a response to the child's behavior. But that child's deep but unconscious anger against the parent may be projected onto the parent.

(5) The practice of psychotherapy

Let me add a final observation about Freud's contributions. It centers on the practice of psychotherapy itself. I need to point out that the consulting rooms of physicians have been the scenes of narrative exchange for millennia. In fact, dream interpretation was not an original contribution by Freud but can be found in the practices of ancient Greek medicine two thousand years earlier.

Freud's insight that healing begins with the telling of the patient's own story – as incomplete and filled with distortions as it might be – serves in some way as his signal contribution. He elaborated an extensive set of interpretative principles and practices that served to structure the encounter of patient and analyst. And these have been subject to so many changes and challenges that we sometimes forget about his advocacy of the more basic commitment in therapy of one person encountering another with the intent of a narrative exchange.