This page was last modified on January 22, 2026

PSY 355 Psychology & Media in the

Digital Age

This page was last modified on January 22, 2026 |

Alter's (2017) Irresistible: Some Notes

Prologue

Behavioral addiction consists of six ingredients:

- compelling goals that are just beyond reach

- irresistible and unpredictable positive feedback ("surprise")

- a sense of incremental progress and improvement

- tasks that become slowly more difficult over time (avoiding boredom)

- unresolved tensions that demand resolution

- strong social connections

Addictions are damaging because they crowd out other essential pursuits, from work and play to basic hygiene and social interaction (p. 10)

Note from VWH: In psychiatry, the diagnosis of a psychiatric illness requires that supposed illness have a negative impact upon the individual in at least one of the following ways: (1) personal distress or disability, (2) significant interference with the ability to work productively, interact with others socially, or take care of one's own health, or (3) puts the individual in significant danger of harm.

Chapter 1: The Rise of Behavioral Addiction

On p. 15, Alter presents data showing that individuals average 3 hours every day using their smart phones. Further, 12% use their phones 4-5 hrs/day and 11% more than 5 hrs/day.

A behavior is addictive only if the rewards it brings now are eventually outweighed by damaging consequences. Breathing and looking at wooden blocks aren’t addictive because, even if they’re very hard to resist, they aren’t harmful. Addiction is a deep attachment to an experience that is harmful and difficult to do without. Behavioral addictions don’t involve eating, drinking, injecting, or smoking substances (p. 20)

Note from VWH (1): Alter's book was published in 2017 and was based on statistics from before that date. In the subsequent 4 years, the average time spent in front of screens has increased. Most research in the United States suggests an average use of smart phones at just over 5 hours per day. Other data from 2025 (Wheelwright, 2025) show:

Americans check their phones 186 times per day (11.6 times per hour)

- 72.2% use their phone at work

- 87.4% use their phone while watching TV

- 56.4% use their phone while eating dinner

- 67.9% use their phone on the toilet

- 60.7% have texted someone in the same room

- 49.6% sleep with their phone at night

- 41.3% feel panic/anxiety at <20% battery

- 84.6% check their phone within 10 minutes of waking

- 76.3% feel uneasy leaving their phone at home

- 45.8% consider themselves “addicted” to their phone

- 53.1% have never gone longer than 24 hours without their phone

- 40.1% use their phone on a date

- 29.3% use their phone while driving

- 82.7% are on an unlimited mobile plan

Note from VWH (2): Currently the evidence for gambling and Internet gaming as behavioral addictions is quite strong. There is still argument whether there is a real addiction to the Internet. We'll continue to discuss this. Other possible behavioral addictions with less evidence include hypersexual disorder, compulsive shopping, excessive exercise, food addiction, and addiction to UV (ultraviolet) tanning.

Chapter 2: The Addict in All of Us

In the early 1970s as Vietnam soldiers are returning to the US, 35% of them had tried heroin and 19% were addicted. The US Government feared the return of 100,000 addicts and their impact on the US (see Hall & Weier, 2016; Robbins, 1974).

Research study in 1974 by Dr. Lee Robins of Washington University (St. Louis, MO) found

- 95% of heroin addicts in the US relapsed or failed to stay clean after giving up heroin

- 95% of Vietnam veterans once back in the US remained clean and did not relapse

- WHY?????

This lead to the downfall and rejection of theories that addiction was a "personality defect" or something "inborn"

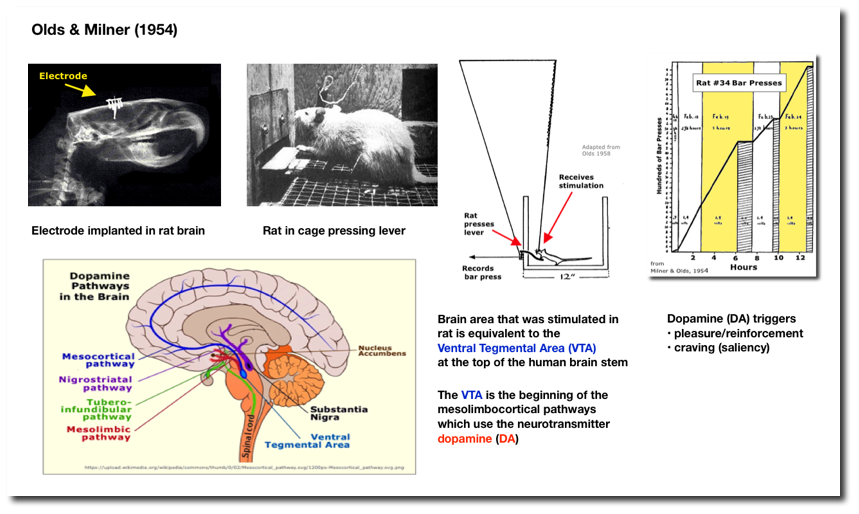

Chapter 3: The Biology of Behavioral Addictions

What is the brain's response to higher levels of dopamine (DA)?

- Increased levels of DA triggers the brain to try to restore a balance in the overall levels of DA.

- As a result it tends to do at least two things which lead to "tolerance"

- It does not release as much dopamine as it had done before (the stimulus [consumption or behavior]) is no longer as surprising or unpredictable

- It decreases the number of dopamine receptors throughout the brain

Research by Kent Berridge in the 1990s and 2000s found that addicts don't just like the effects of their addiction, they also have intense cravings or wantings even if their addiction substance/behavior no longer gives them any pleasure. There are two different feeling states: liking vs. wanting (Robinson & Berridge, 2001).

- Addicts, therefore, must increase their use of the substance or the behavior in order to achieve the same level of pleasure.

- The mesolimbocortical system which uses DA becomes particularly sensitized on a long-term basis to the effects of DA. This, in turn. leads to addicts craving even when they know that the substance/behavior is both harmful and no longer enjoyable.

- More specifically, the brain becomes hyper-reactive particularly to the environmental cues that are associated with the substance/behavior.

- Recall the Vietnam Veterans study: since these veterans were no longer in the same situations as Vietnam (jungles, being shot at, hearing the sounds of explosions or helicopters, etc.) the environmental cues for drug use were not there and their craving for heroin tended to go away.

Contemporary theories about the role of dopamine emphasize that it is strongly released when an individual experiences something that is surprising or not expected.

"“…dopamine helps us select the best actions and thoughts for achieving particular goals – do more of that, it tells the rest of the brain when a goal is achieved. Except there is a twist: success doesn't always result in dopamine. Actually, what causes a burst of dopamine is not just any success, but unexpected success.

Experiments in monkeys and rats show that dopamine release most closely aligns not with the actual reward delivery, but with the surprise: the more unexpected the success, the more dopamine. This changes the "do more of that" logic quite a bit: it implies dopamine is more like a "better than expected" chemical, while its depletion means "worse than expected”.

Rather than thinking of this dopamine jolt into the cortex as a positive, pleasurable signal, I think it makes more sense to think of it as an imperative signal: figure this out. For the cortex, "figuring out" means aligning reality and expectation, and you can do that by either changing reality or changing expectations. I would guess that dopamine must shift the balance of forces toward changing reality, compelling us to act rather than accept the state of things as they stand.” (emphasis added; Kukushkin (2026)

References

Hall, W., & Weier, M. (2016). Lee Robins’studies of heroin use among US Vietnam veterans. Addiction. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.13584

Kukushkin, N. (2026, Jan 16). What we get wrong about dopamine. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20260116-what-we-get-wrong-about-dopamine

Robins, L. N. (1974, May) The Vietnam drug user returns (Special Action Office Monograph, Series A, No. 2). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2001). Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction, 96, 103-114. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9611038

Wheelright, T. (2025, Jan 1) Cell Phone Usage Stats 2026. Reviews.org. https://www.reviews.org/mobile/cell-phone-addiction/#Cell_Phone_Usage_and_Habits