This page was last modified on October 3, 2024

PSY 355 Psychology & Media in the

Digital Age

This page was last modified on October 3, 2024 |

Class 14: The Neuropsychology of Media • II • The Automobile as Digital Device

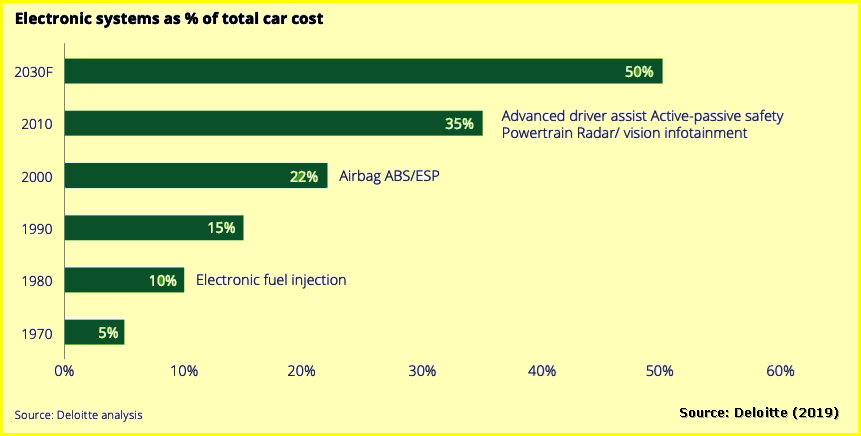

- As it evolved over the past 40 years, the modern automobile has become, in many ways, a hybrid mechanical-digital device.

- As seen above, the average new car today has 2 1/2 times more computer code in its digital processors than the operating system of a personal computer and more than 6 times as much code as the modern passenger jet plane.

- “Today, a car can have well over 50 separate computer systems…” (Computer chips inside cars, n.d.)

- “Estimates say that there are roughly around 1,000+ [semiconductor] chips in a non-electric vehicle and twice as much in an electric one.” (How many chips…, 2022). These computer systems and semiconductor chips carry out a vast number of tasks as shown in the image below.

The Automobile as Media Setting

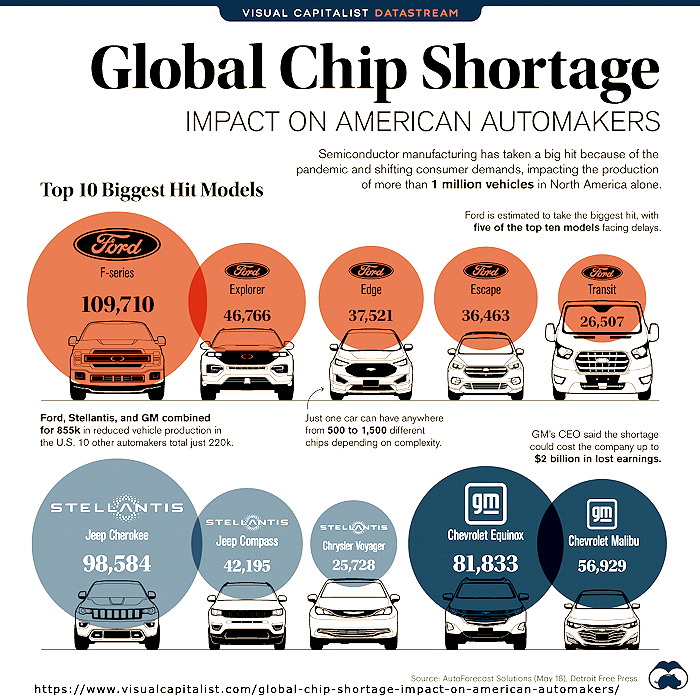

- Of course, beginning in March 2020 because of the pandemic and the problem of supply chain delays, the American automobile manufacturers have had major difficulties in obtaining the computer chips necessary for their vehicles. (MotorTrend Magazine)

- Many of the new additions to the car's mechanical systems have increased its fuel efficiency and, as we will see below, provided many important safety features. Yet, an automobile is no longer just a means of transportation.

- In the United States, the first automobile radios first appeared in cars in the 1930s during the Great Depression. They were very expensive and only provided AM radio coverage. FM radio units were introduced in the early 1950s. The advent of the transistor (and low voltage tubes) in the late 1950s and early 1960s made AM/FM radios much cheaper and widespread in American autos.

- The first 8-Track tape players to listen to recorded music arrived in 1965 and, soon thereafter, the first built-in cassette tape player appeared.

- Compact disk (CD) players arrived in the mid-1980s and, at first, were only available on high-end (expensive) cars. During the 1990s, more and more automobile had CD players as an affordable option.

2023 Honda Civic • Best Affordable Compact Car (USNWR)

MSRP of $25,050-43,295

- 7-Inch Color Touch-Screen with Apple CarPlay® and Android Auto™ Compatibility

- Bluetooth® streaming audio

- Steering-wheel-mounted audio & driving controls. All Civic steering wheels have two sets of controls. The left-hand set operates the audio system and 7-inch Driver Information Interface (DII). The Bluetooth® HandsFreeLink® and the navigation system voice-recognition button are on the left as well. The right-hand set operates the Lane Keeping Assist System11 (LKAS) Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) with Low-Speed Follow

- Bose Premium Sound System

-All systems also provide Speed-Sensitive Volume Compensation (SVC); as the car speeds up and exterior noise increases, the audio system automatically raises the music’s volume, and then lowers it as the car slows down.

- Adaptive cruise control, lane departure warning, traffic sign recognition and automatic stop system.

2023 Kia Telluride • Best Midsize SUV (USNWR)

MSRP = $35,690-52,785

- 12.3-inch Touchscreen Display w/ Navigation, Kia Connect & SiriusXM® Satellite RadioThe contemporary automobile (car, wagon, SUV) serves as a hybrid media form which provides

- Rear-View Monitor w/ Dynamic Parking Guidance

- Apple CarPlay® & Android Auto™

- Bluetooth® Wireless Technology w/ Multi-Device Connectivity

- Wi-Fi Hotspot

- Smart Cruise Control w/ Stop & Go

- USB-C Fast Charging Ports, 5

- Rear seat entertainment (RSE) center:Two monitors and two remotes. Provides USB ports. New available APP's: Pinkfong (For Kids), News (CNN, Fox News), Games. RSE currently does not support Apple CarPlay or AirPlay. [Cost: an additional $1400]

- a means of transportation

- an "infotainment" or "in car entertainment" (ICE) media center

- Infotainment = "information-based media content or programming that also includes entertainment content in an effort to enhance popularity with audiences and consumers" (Demers, 2005, p.14)

- In car entertainment (ICE) = "a collection of hardware devices installed into automobiles, or other forms of transportation, to provide audio and/or audio/visual entertainment, as well as automotive navigation systems (SatNav). This includes playing media such as CDs, DVDs, Freeview/TV, USB and/or other optional surround sound, or DSP systems. Also increasingly common in ICE installs are the incorporation of video game consoles into the vehicle." Wikipedia.

- A relatively new phenomenon, i.e., advanced "infotainment" systems in cars introduced about 2010 (Vance & Richtel, 2010).

Elements of in car entertainment might include

- Sound: AM/FM/satellite radio; CD & MP3 players; cassette player; telephone; BluTooth wireless or audio input jack connections for cell phones, iPads, etc.; text-to-audio voice-activated texting or messaging system

- Vision: GPS* navigation; in-dash information center (speed, direction, gas usage...); DVD; game consoles;

- WiFi connectivity for passenger Internet use

- Driving controls: turn signals, wiper controls, cruise controls, light controls (lo-hi beam); OnStar emergency, security, navigation, and other passenger safety systems

Navigation in Cars

GPS = Global Positioning System which is "a space-based satellite navigation system that provides location & time information in all weather conditions, anywhere on or near the Earth where there is an unobstructed line of sight to four or more GPS satellites" {W}

- Developed by the US Defense Dept. in the 1970s and made accessible to the general public by Pres. Bill Clinton in a 1996 executive order operative in 2000.

- The system relies upon a minimum 24 satellites (there were 31 in operation as of 11/6/2020 and another 9 being held in operational reserve and 3 more being tested)

- The signals from the GPS are accurate to within 20 meters (66 ft) anywhere on earth.

NEW: What3Words.com

- What3words is a proprietary geocode system designed to identify any location on earth with a resolution of about 3 metres (9.8 ft). It is owned by What3words Limited, based in London, England. The system encodes geographic coordinates into three permanently fixed dictionary words. For example, the front door of 10 Downing Street in London is identified by ///slurs.this.shark. [Wikipedia]

- What3words divides the world into a grid of 57 trillion 3-by-3-metre squares, each of which has a three-word address. The addresses are available in forty-seven languages. [Wikipedia]

- Each what3words language uses a list of 25,000 words (40,000 in English, as it covers sea as well as land). The lists are manually checked to remove homophones and offensive words. [Wikipedia]

For example: "sings.rail.home" is the What3Words location for part of this classroom (207) in Grewen Hall

- What3Words has partnered with multiple automobile companies (particularly those who see high-end or expensive cars such as Mercedes-Benz and Lamborgini) to integrate the What3Word app into the geolocation/navigation system of the car. A driver can simply use the 3 word address of the car's destination and the What3Words system will bring the car to the exact location specified. The system is designed so that the driver simply has to say the three words out loud or can enter the 3-word address as text into their app.

Traffic Fatalities & Improving Car Safety

- In the 50 years between 1922 and 1973, the absolute number of deaths due to motor vehicles generally grew (except for the period of the 2nd World War when fuel was rationed). Then, in the last quarter of the 20th century and into the 21st century, despite the steady growth of the population, the absolute number of motor vehicle deaths steadily decreased.

- The safety of automobile operation steadily and continuously improved between 1922 and the early years of the 21st century as seen in the lowered number of deaths per million vehicle miles traveled (VMT).

- Why the increased level of safety? Cars were massively improved in terms of both structural and safety design (think: safety belts). Highway design further made driving safer (think: divided highways, light reflectors on the sides of the road at night, improved barriers)

- The data above come from the National Transportation Safety Administration (NTSA)

- Death rates in 2019 were down 1.2% from 2018 and 3.1% from 2017

- BUT, in both 2020 & 2021 death rates increased over 2019 (18.7% higher)

- There were 4.8 million injuries in motor vehicle accidents in 2020 (up from 4.2 million in 2019)

- Traffic accidents, fatalities, and injuries cost a total of ~ $474 billion in the United States

Why are the rates of dying in traffic accidents higher in recent years than they were 8 to 10 years ago?

There are at least two hypotheses which can help explain these data:

Hypothesis 1: Heavier American cars are much more lethal in crashes

Hypothesis 2: American drivers are distracted by electronic devices (both handheld and on the dashboard)

Hypothesis 1: Heavier American cars are much more lethal in crashes

In a very recent report in The Economist, research has pointed to the dual conclusions that (1) drivers and passengers in heavier cars like pick-up trucks are less likely to die in a crash compared to lighter cars, BUT, (2) heavier cars like pick-up trucks are far more lethal in crashes and cause much higher rates of death ("Too much of a good thing," 2024, August 31).

Distracted Driving: Measuring the Effects (Strayer et al., 2011, 2013; Wilson & Stimpson, 2010)

- According to the CDC, approximately 2800 people died and 400,000 injured in crashes involving a distracted driver in 2019. 20% of those who died were actually pedestrians, bicyclists, or otherwise outside a vehicle. While this decline in 2019 is notable, between 2010 and 2017 roughly 3,100 distracted driving deaths occurred each year.

- Multivariate analyses indicated that texting resulted in more than 16,000 additional road fatalities between 2001 and 2007.

- General driver inattention is a factor in upwards of 78% of all crashes & near crashes (Dingus et al., 2006)

- Sources of distraction in driving (Stayer et al. 2011) include

- Visual Processing Competition: Driver doesn't look at road in order to look at dash-board or other device

- Manual Interference: Driver takes hands off wheel in order to manipulate a device

- Cognitive Distraction: Driver withdraws attention from processing road- and safety-related information in order to accomplish another cognitive task.

- Each of these sources acts independently and can also interact with one another.

Past research has shown

- Drivers who are using a cell phone tend to experience "inattention blindness" where the conversation on the phone diverts the driver's attention from processing the information needed for safe driving (p. 7).

- Similarly cell phone-using drivers show alterations in brain wave activity in the form of Event-Related Brain Potentials (ERPs). In this situation, drivers do not code the information before them in the driving scene as well as they do without conversation and reaction times are slowed.

- Drivers engaged in a second cognitive task exhibit a form of "tunnel vision" in which they keep their eyes looking ahead and do not glance at the sides of the road as frequently as non-distracted drivers.

Experimental Set-up

Tasks

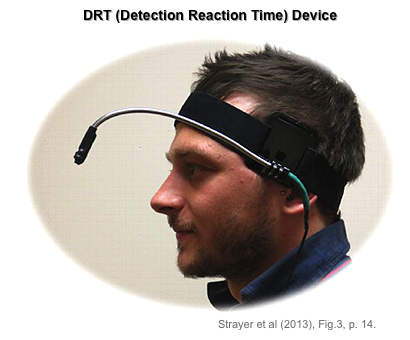

1. None: Simple driving, no other taskParticipants were fitted with a DRT (detection reaction time) headset in which they were presented a random series of either red or green signals off to the side of their forward vision. This approximates what drivers may experience when traffic lights are positioned at the side of a street. Subjects were also fitted with an EEG (electro-encephalogram) recording device to measure changes of attention when facing red-green light change. This measurement focused upon ERPs and, especially, what is called the P300 brain wave which marks when a subject's attention has changed (see further description below).

2. Radio: Driving while listening to a radio

3. BookOnTape: Driving while listening to a book on tape

4. Passenger: Driving while holding 10 min. conversation with passenger

5. Handheld: Driving while holding 10 min. conversation on a hand-held cell phone

6. HandsFree: Driving while holding 10 min. conversation with a hands-free cell phone

7. Speech-Text: Driving while interacting with a speech-to-text interfaced email system

8. OSPAN: Driving while performing auditory version of the OSPAN mental processing tasks (math & memorization)

Experiment 1: Laboratory Control (Baseline)Some Results

Experiment 2: Driving Simulator

- In front of a computer without actually driving, but performing the 8 tasks

Experiment 3: Instrumented Vehicle (in Real Life)

- In a realistic car simulator performing the 8 tasks

- Driving a 2.75 mile loop in a suburban section of Salt Lake City Utah while performing the 8 tasks. The driver was accompanied by both a researcher and an assistant who had a redundant set of brakes.

The first diagram shows the time delay of the event-related potential's P300 peak latency brain wave. What does this measure? Event-related potentials (ERP) are an objectively non-invasive approach for studying information processing and cognitive brain functions, such as attention, learning, memory, and decision-making…Sutton et al. [1965] first reported a evoked potential component that reached its peak amplitude at approximately 300 ms and found a significant association between this ERP component and cognitive function…The P300 is an important and extensively explored late component of ERPs that is widely applied to assess cognitive function in humans. The amplitude and latency of the P300 component provides information about cognitive processes in the brain, such as memory, attention, concentration and speed of mental processing…The P300 component has been considered a potential marker of cognitive dysfunction… (Zhong et al. 2019)

Some Other Research Findings

- Drivers who are 15–20 years of age constitute 6.4% of all drivers, but account for 10% of all motor vehicle deaths, and 14% of police-reported crashes (Trivedi et al. 2017)

- "According to the results of a 2015 US national survey, the percentages of drivers ages 19–24 reporting engaging in the following behaviors at least once while driving in the past 30 days were as follows: 59% read a text/email, 45% typed/sent a text/email, and 77% talked on a cell phone, all increased from results of the same survey conducted in 2014 (AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, 2015)" (Trivedi et al. 2017, p. 451)

- In the Youth Risk Survey, 2019, teenage drivers reported significant levels of texting or emailing while driving including 31% of 16-year-olds, 51% of 17-year-olds, and 60% of 18-year-olds.

- Distracted driving is about equally common among middle aged adults as among teenagers. Older drivers (> 65 years old) tend NOT to engage in distracted driving (Pope et al., 2017)

- In one study of adults aged 30-64 (Female 75%, White 69%), 65% reported texting when stopped at red lights and 20% spending about 25% of their time in a car talking on a cell phone. Cell phone users said (1) they were confident of their ability to drive while talking/texting or (2) they were obligated to take calls related to their work (Engelberg et al., 2017)

- In a naturalistic study of 83 newly licensed teenage drivers in Virginia (53% female; average age 16.5 years), researchers installed video recording, accelerometer, & GPS tracking devices to observe/record driver behavior. They found 58% of the time that drivers were engaged in at least one task secondary to driving: (1) interacting with another passenger [20%], (2), talking/singing by self with no passenger [17%], (3) attending to external distractions outside car (12%); and (4) manual cellphone use (texting/dialing/browsing 5%). (Gershon et al. 2017)

ABC Nightline: Caught On Tape: Teen Drivers Moments Before a Crash

(AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety YouTube: 6'45" Mar, 2015)

==> Let me ask you to consider the following questions:

- What are the different sources of distraction you have noted in driving (beyond texting itself)

- What have you seen happening, e.g., with your parents, your friends, others?

- Is there anything that you think could convince people to drive in a safer way?

References

Computer chips inside cars (n.d.). https://www.chipsetc.com/computer-chips-inside-the-car.html

Deloitte (2019, April). Semiconductors-the next wave. Downloaded from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/cn/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/deloitte-cn-tmt-semiconductors-the-next-wave-en-190422.pdf

Demers, D. (2005). Dictionary of mass communication and media research: A guide for students, scholars and professionals. Spokane, WA: Marquette Books.

Dingus, T. A., Klauer, S. G., Neale, V. L., Petersen, A., Lee, S. E., Sudweeks, J., Knipling, R. R. (2006). The 100-car naturalistic driving study: phase II -- Results of the 100-car field experiment. Washington, DC: DOT HS 810 593.

Healey, J. R. (2014, Feb. 25). 'Consumer Reports:' Cars better, infotainment not. USA Today. Retrieved at http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/cars/2014/02/25/consumer-reports-worse-infotaiment-reliability/5794281/

How many chips are in our cars? (2022, May 4) Electronics Sourcing [Online]. https://electronics-sourcing.com/2022/05/04/how-many-chips-are-in-our-cars/

McKinsey & Co. (2020, March). Cybersecurity in automotive: Mastering the challenge. Downloaded from https://www.gsaglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Cybersecurity-in-automotive-Mastering-the-challenge.pdf

Ramsey, J. (2020, May 11). 40% of a new car's cost is electronic systems. Autoblog.com. Downloaded from https://www.autoblog.com/2020/05/11/car-electronics-cost-semiconductor-chips/

Strayer, D. L., Cooper, J. M., Turrill, J., Coleman, J., Medeiros-Ward, N., & Biondi, F. (2013, June). Measuring cognitive distraction in the automobile. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. Retrieved from https://www.aaafoundation.org/sites/default/files/MeasuringCognitiveDistractions.pdf

Strayer, D. L, Watson, J. M., & Drews, F. A. (2011). Cognitive distraction while multitasking in the automobile. In B. Ross (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation, Vol. 54 (pp. 29-58). Burlington, VT: Academic Press.

Tauib, E. (2021, March 16). Carmakers strive to stay ahead of hackers. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/18/business/hacking-cars-cybersecurity.html

Too much of a good thing. (2024, August 31) The Economist [Online]. https://www.economist.com/interactive/united-states/2024/08/31/americans-love-affair-with-big-cars-is-killing-them

Vance, A., & Richtel, M. (2010, Jan 6). Driven to distraction - Despite risks, carmakers integrate the web with the dash. New York Time. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/07/technology/07distracted.html

Wilson, F. A., & Stimpson, J. P. (2010). Trends in fatalities from distracted driving in the United States, 1999-2008. American Journal of Public Health, 100(11), 2213-2219. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.1871

Zhong, R., Li, M., Chen, Q., Li, J., Li, G., & Lin, W. (2019) The P300 event-related potential component and cognitive impairment in epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 10, Article 943. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00943

This page was first posted on 2/27/14