|

|

PSY 340 Brain and Behavior Class 41: Mood Disorders |

|

|

|

PSY 340 Brain and Behavior Class 41: Mood Disorders |

|

In a change from DSM-IV which used the general category of "Mood Disorders," the DSM-5 (2013) now divides these diagnoses between separate categories of "Depressive Disorders" and "Bipolar and Related Disorders."

A. Major Depressive Disorder (DSM-5)

Psychiatric Interviews for Teaching: Depression (2012) University of Nottingham, UK YouTube (14'44") |

|

Individuals with Major Depressive

Disorder tend to have the following types of symptoms:

Individuals with Major Depressive

Disorder tend to have the following types of symptoms:

- feel sad, helpless, and lacking in energy and pleasure for weeks at a time

- experience little pleasure from activities that used to be pleasurable (e.g., sex or food) = "anhedonia" (= no + pleasure)

- feel worthless or guilty

- experience fatigue or loss of energy

- have trouble sleeping (too much or too little)

- gain/lose significant amount of weight in short periods (+/- 5% of body weight)

- have trouble concentrating

- contemplate or think about death and suicide

In the previous class on Schizophrenia, we saw that Depressive Disorders were the major cause for inpatient hospitalization in the United States (2016-18) while Bipolar Disorders (discussed below) were the 3rd major cause of inpatient hospitalization.

Note as you examine the national map of the inpatient hospitalization rates that

there are wide disparities among the 38 states for which we have data.

Gender & Age: Incidence & Prevalence (https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression)

- Depression is about twice as common among adult women than adult men across the life span in cross-cultural studies in the US and elsewhere

- 12-month prevalence in the United States among all adults in 2021 was 8.3% (ca. 21 million American adults)

- In US, one-year prevalence was 6.2% in men & 10.3% in women in 2021 (https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression)

- However, young adults (18-29 years old) were more than 4 times as likely to experience MDD as adults over age 50: 18.6% vs. 4.5%

- In US, lifetime incidence is ca. 12% in men & 20% in women (Belmaker & Agam, 2008)

Childhood depression appears to be equally common in boys and girls before 13 years of age.

- The estimated prevalence among pre-schoolers and pre-pubescent children is around 2%.

- However, among adolescents between 13 and 18, the rates become much higher: 7.5% 12-month prevalence and 11% lifetime incidence with girls being twice as likely to be diagnosed as boys (Pataki & Carlson, 2016)

- These data from before the Covid-19 pandemic have been supplanted as the rates of depression, anxiety, and other forms of mental disorders among children and adolescents have risen in the past 5 years.

- Latest data shows increase of depression in youth 3 to 17 years old from 3.2% (95% CI 2.9%-3.5%) in 2016 to 4.6% (95% CI, 4.2%-4.9%) in 2022 (Heffernan & Macy, 2025)

- Similarly, the rate of anxiety has also increased post-pandemic: from 7.1% (95% CI, 6.6%-7.6%) in 2016 to 10.6% (95% CI, 10.1%-11.2%) in 2022

1. Genetics

- Evidence of genetic or other biological predispositions to depression shows a moderate degree of heritability. Monozygotic vs. dizygotic twin concordance rates suggest a heritability of ca. 37% (Belmaker & Agam, 2008) but may be higher for early-onset (before 30 yo), severe, or recurrent depression.

- The heritability of depression is lower than the heritability of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

- No single gene for depression has been found. Because significant early-life stresses ARE associated with higher risk of depression, researchers has sought to document a gene x environment effect = certain genetic vulnerabilities interact with stressful environments to produce depression.

- A particularly influential study which is cited by our text involves the Serotonin Transporter Gene (5-HTTT) Stress Sensitivity Hypothesis of Caspi et al (2003). They examined 847 young people in their early 20s from Dunedin, New Zealand, all of whom had been part of a longitudinal study since early childhood. Their data showed that individuals with a variant gene with particularly low levels of serotonin transporter proteins were especially at risk for severe depression when exposed to a lot of stress compared to those whose gene variant produced a lot of serotonin transporter protein. Indeed, our text includes a figure from the 2003 study.

- Though Caspi et al (2003) has been widely cited, more recent and broader research has actually overturned their specific conclusion of a gene x environment effect. Culverhouse et al. (2017) performed new analyses on 31 different data sets of more than 38,000 participants for whom both genetic and life-history data were available. They found "no subgroups or variable definitions for which an interaction between stress and [the 5-HTTT gene variants] was statistically significant." (Abstract). They did find that two variables (life stressors and female sex) WERE each strong and independent risk factors for the development of depression.

- A recent major GWAS of depression among 689,000 participants with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and 4.4 million controls from 29 countries across the globe found 697 genetic markers for the development of MDD at 635 positions on chromosomes of which 293 were not previously known (Adams et al., 2025). However, the overall ability to predict MDD based on these genetic variants is quite modest: about 6%.

2. Course of Depression

- Depression is usually episodic, not constant: episode generally lasts about 6-7 months.

- Someone may feel normal for varying periods -- weeks, months, or years -- between episodes of depression.

3. Postpartum Depression (not in book)

- Most women experience the blues for a day or two after giving birth.

- About 20% experience moderate postpartum depression (depression after giving birth) and 1/10 of 1% experience very severe postpartum depression.

4. Brain Functioning and Structure

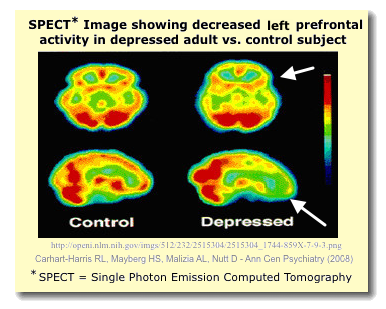

- Most people suffering from depression have decreased activity in the left prefrontal cortex and increased activity in the right prefrontal cortex. This is consistent with the information we saw about the frontal area of the right hemisphere as more prone to pessimism and negative emotional outlook.

- Left hemisphere brain damage leads to more severe depression than right hemisphere damage.

More recent studies have shown that there is "strong and consistent evidence of decreased volume of cortical and limbic brain regions—such as the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the hippocampus—that control emotion, mood, and cognition, suggestive of neuronal atrophy that is related to length of illness and time of treatment" (Duman & Aghajanian, 2012, p. 68, emphasis added). The size of cells in both the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus has been reported as smaller than normal (see below the role of BDNF). And, further, postmortem and brain imaging studies of stress-related depression show overall decrease in the number of dendritic branches, dendritic spines, and overall synaptic complexity (Duman, 2009/2022).

5. Antidepressant drugs: Drugs used for the treatment of depression and other mood disorders. These drugs fall into four categories and affect the catecholamines (epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine [NE] (noradrenaline), & dopamine [DA]) and/or serotonin [5-HT].

a. Tricyclics: Prevent the presynaptic neuron from reabsorbing catecholamines or serotonin after releasing them (this allows the neurotransmitter to remain longer in the synaptic cleft thus stimulating postsynaptic receptors).

b. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): These drugs are similar to tricyclics, but are specific to the neurotransmitter serotonin. The most popular drug in this class is fluoxetine (Prozac®).

c. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): Block the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO) from metabolizing catecholamines and serotonin into inactive forms. Usually used as a drug of last resort because it requires a strict diet to avoid certain foods.

d. Atypical Antidepressants: A miscellaneous group of drugs with antidepressant actions and mild side effects, including

- bupropion (Wellbutrin®), which inhibits reuptake of dopamine and to some extent norepinephrine

- venlafaxine (Effexor®), which inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine; and

- nefazodone (Serzone®), which specifically blocks serotonin type 2A receptors and blocks reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine.

e. St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L) is an herbal treatment of depression (Linde et al., 2008)

- Appears to increase the availability of serotonin

- More effective than placebo for major depression

- As effective as antidepressant medications (particularly in studies done in Germany)

- Side-effects lower than among standard antidepressant medications

- WARNING 1: A liver enzyme triggered by St. John's wort tends to break down other medications very fast, e.g., cancer & AIDS drugs, birth control pills. Hence, a doctor needs to be consulted if you are taking any other medications.

- WARNING 2: Since this is an unregulated compound, dosages & purity vary.

f. Time: Delayed Effects: Most of antidepressants have delayed effects, i.e., they require 2-3 weeks for beneficial effects to appear.

- Antidepressants don't appear to work by directly acting on the synapse. Rather, after changing synaptic activity patterns, such changes trigger further changes which are responsible for beneficial effects.

- A possible reason for the delay may involve a gradual increase in the release of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), a neurotropin which may cause an increase in cell size (esp. to counteract smaller cell size in hippocampus and cerebral cortex). In animal models of depression linked to stress, cortisol causes decreases in BDNF expression which may lead, in turn, to cell damage in the hippocampus et al. Many human persons with depression can identify a significant period of stress before they became depressed.

- Another effect may be to desensitize the autoreceptors (a negative feedback receptor on the presynaptic terminal; see diagram above) increasing the release of neurotransmitters such as serotonin.

Ketamine {W} and other NMDAR Antagonists as Rapid Treatment for Depression

- Ketamine is a nonselective N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonist, that is, it blocks the action of the NMDA receptor. Glutamate, the excitatory transmitter, binds to NMDARs which are found throughout the nervous system (including the membrane of both neurons and glial cells [astrocytes]). However, there are also NMDARs on GABAergic neurons in the nervous system as well. It may be that Ketamine has its effects on those GABAergic neurons.

- Ketamine is a human & veterinary drug used as a general anesthetic in surgery. It is also a recreational drug of abuse ["K" "Special K" etc.] {W} because it causes a dissociative state similar to PCP and other hallucinogens. Prolonged use even at low doses can cause long-term physical damage to the NMDARs and is similar in severity to anabolic steroids or inhalation of solvents. This is to say that Ketamine is a drug which has powerful and significant side effects.

- Experiments have indicated that low doses of intravenously-injected Ketamine may be clinical useful in treating patients with severe forms of depression. What is surprising is that treatment effects are seen within hours rather than days or weeks. However, the symptoms return without continued medication in 7-10 days.

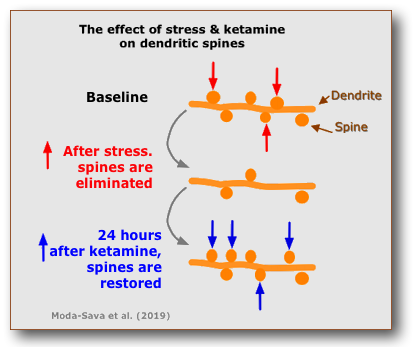

- Why it may have this effect is unknown at present. Multiple researcher believe that Ketamine causes a rapid increase in (1) the number of synaptic connections in various areas of the brain and (2) reversal of stress-induced atrophy of cortical tissue. However, as Pochwat et al. (2019) note, "“No existing hypothesis explains the exact molecular and cellular mechanisms of action of ketamine and other NMDAR antagonists" (italics added). Another commentator argues: "Anyone who tells you that they know how ketamine works for depression is kidding themselves” (Lowe, 2023).

- Another researcher (Mittenrauer, 2012) hypothesizes that "in therapy-resistant depression a significant excess of NMDA receptors in astrocytes is causing a severe lack of glutamate which cannot be balanced by reuptake inhibitory drugs...[Hence,] the blockade of the excess of NMDA receptors [by Ketamine] in astrocytes may rapidly balance synaptic information processing" (p. 2).

- On March 16, 2019, the FDA approved the first nasal stray for treatment-resistent depression, Spravato™, which must be used along with an oral antidepressant medication. The active ingredient of Spravato™ is Esketamine, a molecule similar to but not ketamine. As the figure on the right shows, Esketamine is an antagonist of the NMDA receptor, one of the three types of glutamate receptors.

- We know that long-term stress damages the spines of dendrites, that is, the point at which neurons synapse with other neurons; they wither away. Such damage is believed to be important in the symptoms of depression. In an important 2019 study, Moda-Sava and colleagues report that mice which have stress-induced damage to dendritic spine respond within 24 hours to a dose of ketamine with the growth of new dendritic spines and lowered depression-like behaviors (see figure above). See, e.g., Kuntz (2021).

g. Controversy: Because anti-depression medications appear to increase the amount or availability of serotonin, researchers in the late 20th century spoke about the Serotonin Hypothesis of Depression = depression is caused by too little serotonin in the brain.

Increasingly neuroscientists reject the "Serotonin Hypothesis of Depression" completely or substantially because they dispute the effectiveness of antidepressant medications based upon increasing levels of serotonin

- Irving Kirsch: The Emperor's New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth (2010)

- Antidepressant medications work no better than placebos (note: the placebo effect can be very powerful!)

- University of Pennsylvania researchers (Fournier et al. 2010) reexamined the six most rigorous studies of the effectiveness of antidepressants vs. placebos. (See diagram: green area on right)

- Patients with mild to moderate depression show relatively little benefit from antidepressant medications

- Patients with severe depression respond "substantially" to medications over a placebo

6. Non-Drug Therapies

a. Psychotherapy (particularly, cognitive therapy & interpersonal therapy) and drug therapies produce similar effects on brain activity. Patients who recover using psychotherapy are less likely to relapse, but it takes up to twice the time to get benefits from psychotherapy as compared to drug treatments, i.e., 4 to 8 weeks rather than 2 to 3 weeks.

b. Exericse. Physical exercise has been broadly shown to be effective in relieving symptoms of mild to moderate depression. Stanton & Reaburn (2014) found particular benefit from supervised aerobic exercise programs undertaken at least three times a week at a moderate level of intensity for at least nine weeks.

c. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

- Inducing seizures with a brief electric shock presented to the right hemisphere. ECT is usually applied every other day for about two weeks. It is effective (60-80%) in relieving the depression in a majority of patients. Why it is effective is currently unknown.

- Side Effects

- Memory loss: mild and usually transient

- About half of those who respond well to ECT relapse into depression within six months unless they are given antidepressant drugs or other therapies to prevent it.

- Used primarily with patients who have NOT responded to medications in the past. These patients are usually severely depressed or agitated and, often, suicidal. And, the most severely depressed patients show the greatest response and effectiveness.

d.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) for Severe, Treatment-Resistant Depression

- Very recent experimental work with patients who have not responded to any form of treatment use deep-brain electrical stimulators

- They are planted deep into the anterior cingulate cortex (see image on right)

- Holtzheimer et al (2012) reported that

- 17 patients (10 with unipolar depression & 7 with bipolar depression) were treated (a) 4 weeks in a "sham" [non stimulated] condition followed by (b) 24 weeks of active stimulation. Patients evaluated for 2 years post-experiment

- Patients had moderate-to-severe depression & had not responded to at least 4 antidepressant treatments

- Majority of the patients experienced significant decrease in depression & increase in ability to cope with daily life. 11 patients were still in remission after 2 years of active stimulation.

- Two patients did commit suicide: a result probably of no treatment working rather than this treatment. A figure consistent with other studies of treatment-resistant patients.

B. Bipolar Disorder

(BD, formerly "Manic-Depressive Disorder")

Bipolar Disorder • Manic State Interview Psychiatric Interviews for Teaching: Mania University of Nottingham |

|

Disorder where the person alternates between episodes of depression and mania. Even during periods of relatively good mood ("euthymia"), individuals with BD often experience wider mood variations or instability than those without the disorder (Harrison et al., 2018).

Mania = persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, and abnormally and persistently increased activity or energy. It is characterized by at least three or more of the following symptoms (DSM-5-TR, 2022):

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep (e.g., rested after only 3 hours of sleep)

- More talkative than usual or pressured to keep talking

- Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing

- Distractibility (easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli)

- Increased in goal-directed activity (socially, at work, sexually) or psychomotor agitation (i.e., purposeless non-goal-directed activity)

- Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, foolish business investments)

1. Bipolar I disorder: A type of bipolar disorder where the person has full-blown episodes of mania.

2. Bipolar II disorder: A type of bipolar disorder where the person has much milder manic phases, called hypomania.

- In the majority of cases (ca. 60%), the manic/hypomanic episode precedes the depressive episode.

- Many individuals with BD have other psychological disorders. "The most frequently comorbid disorders are anxiety disorders, alcohol use disorder, other substance use disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder” (DSM-5-TR, 2022, p. 150).

3. Incidence and Demographics (DSM-5-TR, 2022; Rowland & Marwaha, 2018)

- The 12-month prevalence of BD in the US is ca. 1.5%.

- The mean age of onset of bipolar disorder is in the mid-20s though there is some evidence that there may be two distinctive risk periods: ages 16-24 and 45-54.

- The rates of BPD are generally equal between males and females.

- Among patients with BPD, about 5-6% die by suicide (= 20-30 times greater risk than in general population; DSM-5-TR) and, because of other health risks, life expectancy of BPD patients is about 15 years shorter than the average person (Harrison et al., 2018)

4. There is a strong hereditary basis for bipolar disorder

- Concordance rate for monozygotic twins is at least 50%. The child of a parent with BD has a 5-10% risk of developing the disorder (that is, 5 to 10 times higher risk than in the general population).

- However as is true for most psychiatric diagnoses, no specific gene for this disorder has been located though multiple genes have begun to be identified, each contributing a small degree to the disorder.

5. Neurobiological Factors in BD

- Over and above the genetic/hereditary predisposition for BD, the neurobiological factors underlying the various forms of this disorder are not very well understood.

Some of the neurobiological factors that are receiving attention in research about the underlying pathology in bipolar disorder involve

- Abnormality in the circadian sleep-wake cycle (including disturbed sleeping patterns, heightened sensitivity to light, and abnormal patterns of melatonin secretion)

- Alterations in the Ca2+ (calcium) signalling system in the brain which introduces imbalances between excitatory & inhibitory processes (Berridge, 2014). Note that the circadian sleep-wake processes of the brain are also closely tied to the Ca2+ (calcium) signalling system.

- Dysfunctions of multiple neurotransmitter systems (including DA, GABA, Glutamate) and mitochondria (the energy organelles within all cells including neurons) as well as the impact of various forms of psychological and physiological stress impair the functioning of neurons in the central nervous system, cause cell damage, and lead to the loss of brain tissue (Young & Juruena, 2020).

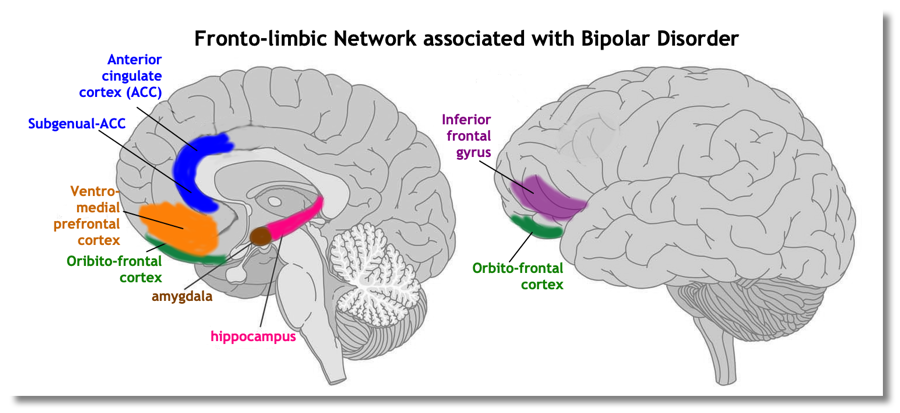

- Brain network disturbances. A meta-analysis of functional MRI studies with about 1,000 persons with bipolar disorder (BD) and 1,000 individuals without BD found significant "activity disturbances in key areas [of the brain]...Most of the regions are part of the fronto-limbic network" which involves areas of the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala (Mesbah et al., 2023, Abstract; see diagram above]. Three sets of cognitive/emotional functions were compared in BD vs. non-BD individuals:

- Emotional Processing: hyperactivation in the hippocampus, parts of the temporal cortex, & amygdala and hypoactivation in the right IFG

- Reward Processing: hyperactivation in the OFC (excessive reward leads to manic symptoms & deactivation gives rise to depressive symptoms)

- Working Memory: hyperactivation in the subgenual ACC and ventromedial PFC (areas which are important for integrating cognitive and emotional stimuli)

6. Treatment

Lithium salts are among the most effective therapies for bipolar disorder (Rege, 2019). In the early part of the 20th century, there were some "patent medicines" and other products containing lithium salts which claimed to have beneficial effects, e.g., as a cure for a hangover. The American soft drink, 7-UP (originally called "Bib-Label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda"), was marked from 1929 to 1948 with lithium citrate as one of its components.

The ability of lithium to reduce the symptoms of bipolar disorder was discovered in medicine by the Australian psychiatrist, John Cade, in 1949. In experiments with guinea pigs, Cade discovered that lithium calmed the animals and he began to use lithium to treat his human patients with manic-depressive disorder (as it was then called). At least half of them improved significantly. His research paper in an obscure journal was widely ignored until more than 20 years later in 1970 when researchers reported in the UK medical journal, The Lancet, the positive experimental effects of lithium on psychiatric patients with manic-depressive disorder.

Lithium is considered a "mood stabilizer" since it also has a protective effect against depressive episodes as well as mania. Although its use has declined in the last thirty years because of fears of some possible side effects, it is one of the few psychiatric medications that has clear anti-suicidal effects. Among other actions, lithium has the effect of

- Inhibiting excitatory dopamine both by decreasing the presynaptic transmission of DA and inactivating post-synaptic G-proteins connected to DA receptors.

- Increasing the level of inhibitory GABA which, in turn, reduces excitatory glutamate. The number of NMDA glutamate receptors is also reduced (down-regulated)

- Stabilizes a range of intracellular messenger systems within neurons.

- Other drug treatments include anticonvulsant drugs such as valproic acid (Depakote®) and carbamazepine (Tegretol®).

- Sleep regulation & consistency has been shown to reduce the intensity of mood swings. Perhaps modern technology (lights, television, etc.) is increasing bipolar disorder by altering sleeping patterns.

- Some recent studies show that light therapy (see below for Seasonal Affective Disorder) is effective in bipolar disorder. BUT, it is given at mid-day, not early in the morning and the amount of time in the light must be very gradually increased.

- Other studies have found that "dark therapy" (patient is kept in a darkened environment from 6 pm to 8 am or uses amber-colored eyeglasses to block blue light) helps to stabilize patients' mood.

- Psychotherapy (10-20 hours over 6 to 9 months) has been shown to help prevent relapses among bipolar patients in recovery.

C.

Seasonal Affective

Disorder (SAD)

= Depression that reoccurs seasonally, usually in the winter.

First identified in the early 1980s as a distinctive subtype of depression (Rosenthal et al., 1984).

1. SAD is most common in the North Hemisphere in those areas where the nights are longer in winter and shorter in summer.

- Those who live in the northern areas of North America and in Europe have higher rates of SAD than those who live in more southern areas.

- Notice in the figure above showing rates in the United States and Sweden that Swedes are much less likely to be depressed during their summer months. Of course, Sweden is located more north than the United States AND the Zhang et al. (2022) data involve participants from both northern and southern regions of the U.S.

- In the extreme European and North American north, native peoples tend NOT to have increased SAD during winter months. This may represent an evolutionary adaptation.

- Individuals who are "morning people" ("Larks") tend to show higher rates of SAD in the winter than those who are "night people" ("Owls")

- There IS a version of SAD that occurs among some people each summer. This form of SAD is not well understood. It may be related to warmth/heat rather than levels of light.

2. It is not completely clear what the cause(s) of Seasonal Affective Disorder may be. Some of the mechanisms that have been noted include

- Disruption in the biological clock (i.e., circadian rhythms) because of the changes in available sunlight in the winter

- Decreased levels of serotonin which may be induced by the decrease in sunlight

- Melatonin levels may be disrupted as well with an increase in melatonin overall leading to feelings of sleepiness.

2. Light Therapy (Phototherapy): uses a very bright light. Patient sits near the light for 45-60 minutes usually each morning or, for some patients, each afternoon. Another approach uses a light which turns on and gradually brightens in the early morning hours = dawn simulation.

A very recent "meta-analysis" (Golden et al., 2005) concluded that

"...[1] bright light treatment and [2] dawn simulation for seasonal affective disorder and [3] bright light for nonseasonal depression are efficacious, with effect sizes equivalent to those in most antidepressant pharmacotherapy trials." (Abstract; brackets/emphasis added)

References

Adam, D. (2013). On the spectrum. Nature, 496, 416-418. https://doi.org/10.1038/496416a

Adams, M. J., Streit, F. … McIntosh, A. M. (2025). Trans-ancestry genome-wide study of depression identifies 697 associations implicating cell types and pharmacotherapies. Cell, 188(3), 640-652.e9. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.12.002

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Belmaker, R. H., & Agam, G. (2008, Jan. 3). Major depressive disorder: Mechanisms of disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(1), 55-68. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra073096

Berridge, M. J. (2014). Calcium signalling and psychiatric disease - bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Cell and Tissue Research, 357(2), 477-492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-014-1806-z

Borsboon, D., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 91-121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

Caspi, A., Hariri, A. R., Holmes, A., Uher, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2010). Genetic sensitivity to the environment: The case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(5), 509-527. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452

Culverhouse, R. C., et al. (2017). Collaborative meta-analysis finds no evidence of a strong interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype contributing to the development of depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 23, 133-142. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.44

Duman, R. S. (2022). Neuronal damage and protection in the pathophysiology and treatment of psychiatric illness: stress and depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(3), 239-255 (original work published 2009). https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/rsduman

Duman, R. S., & Aghajanian, G. K. (2012). Synaptic dysfunction in depression: Potential therapeutic targets. Science, 338, 68-72. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1222939

Fingar, K. R., & Roemer, M. (2022, February). Geographic variation in inpatient stays for five leading mental disorders, 2016-2018 (Statistical Report #288) H•CUP: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved from https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb288-Mental-Disorder-Hospitalizations-by-Region-2016-2018.pdf

Fournier, J. C., DeRubeis, R. J., Hallon, S. D., Dimidjian, S., Amsterdam, J. D., Shelton, R. C., & Fawcett, J. (2010, January 6). Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: A patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA, 303(1), 47-53. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1943

Golden, R. N., Gaynes, B. N., Ekstrom, R. D., Hamer, R. M. et al. (2005). The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: A review and meta-analysis of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(4), 656-662. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.656

Harrison, P. J., Geddes, J. R., Tunbridge, E. M. (2018). The emerging neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Trends in Neurosciences, 41(1), 18-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2017.10.006

Hatalski, C. G., Lewis, A. J., & Lipkin, W. I. (1997). Borna disease. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0302.970205

Heffernan M. E., & Macy, M. L. (2025, April 21). Trends in mental and physical health among youths. JAMA Pediatrics. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2025.0556

Holtzheimer, P. E. et al. (2012). Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(2), 150-158. https://doi.org/10/1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1456

Kirsch, I. (2010). The emperor's new drugs: Exploding the antidepressant myth. Basic Books.

Kuntz, L. (2021, May 2) Ketamine: Not a simple treatment, but a worthy one. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/ketamine-not-a-simple-treatment-but-a-worthy-one

Linde, K., Berner, M. M., & Kriston, L. (2008). St. John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4, Art. No. CD000448. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000448.pub3

Lowe, D. (2023, May 22). What exactly does Ketamine do for depression? In The Pipeline (webblog). American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/what-exactly-does-ketamine-do-depression

Mesbah, R., Koenders, M. A., van der Wee, N. J., Giltay, E. I., van Hemert, A. M., & de Leeuw, M. (2023) Association between the fronto-limbic network and cognitive and emotional functioning in individuals With bipolar disorder - A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 80(5), 432–440. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0131

Mittenrauer, B. J. (2012, Dec. 24). Ketamine may block NMDA receptors in astrocytes causing a rapid antidepressant effect. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2012.00008

Moda-Sava, R. N., et al. (2019). Sustained rescue of prefrontal circuit dysfunction by antidepressant-induced spine formation. Science, 364. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat8078

Murkherjee, S. (2012, April 19). Post-Prozac nation: The science and history of treating depression. New York Times.

Pataki, C., & Carlson, G. A. (2016). Major depressive disorder among children and adolescents. Focus, 14, 10-14. https://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20150037

Pochwat, B., Nowak, G., & Szewczyk, B. (2019). An update on NMDA antagonists in depression. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2019.1643237

Rege, S. (2019, Feb. 9). Lithium’s mechanism of action - A synopsis and visual guide. psychscenehub [Online]. https://psychscenehub.com/psychinsights/lithium-mechanism-action-synopsis-visual-guide/

Richt, J. A., Pfeuffer, I., Christ, M., Frese, K., Bechter, K., & Herzog, S. (1997). Borna disease virus infection in animals and humans. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0303.970311

Rosen, L. N., Targum, S. D., … Rosenthal, N. E. (1990). Prevalence of seasonal affective disorder at four latitudes. Psychiatric Research, 31, 131-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(90)90116-M

Rosenthal, N.E., Sack, D.A., Gillin, J.C., Lewy, A.J., Goodwin, F.K., Davenport, Y., Mueller, P.S., Newsome, D.A., & Wehr, T.A. (1984). Seasonal affective disorder: A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Archive of General Psychiatry, 41, 72-80. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120076010

Rowland, T. A., & Marwaha, S. (2018) Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 8(9), 251-269. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125318769235

Scott, J., & Gutierrez, M. J. (2004). The current status of psychological treatments in bipolar disorders: A systematic review of relapse prevention. Bipolar Disorders, 6(6), 498-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00153.x

Stanton, R., & Reaburn, P. (2014). Exercise and the treatment of depression - A review of the exercise program variables. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(2), 177-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.010

Wirz-Justice, A., Ajdacic, V., Rössler, W., Steinhausen, H.-C., & Angst, J. (2019) Prevalence of seasonal depression in a prospective cohort study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 269, 833-839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0921-3

Young, A. H., & Juruena, M. F. (2020). The neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Current Topics in Behavioral Neuroscience, 48, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2020_179

Zhang, H., Khan, A., Chen, Q., Larsson, H., & Rzhetsky, A. (2021). Do psychiatric diseases follow annual cyclic seasonality? PLoS Biology, 19(7), e3001347. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001347

The first version of this page was posted on May 3, 2005