March 15, 2025

![[Brain Image]](../graphics/head_space.gif)

PSY 340 Brain and Behavior

Class 28: What is an Emotion?

|

March 15, 2025 |

PSY 340 Brain and Behavior Class 28: What is an Emotion? |

|

How would you answer the question below that psychologist Dacher Keltner (2019) poses to his classes?How can we define emotion? In the history of psychology, this has been a notoriously difficult concept to define. Consider how these three biological psychologists above each has a different approach.

“If you could flip a switch and shut off the experience of emotion,

all emotions, from that moment going forward, would you?”

Now, whatever your answer to the question, what is the reason for your answer???

Hierarchy of Terms used in Psychology

Lisa Feldman Barrett (2017, Northeastern University) • Theory of Constructed Emotion

Despite their differences, most psychologists argue that an emotion comprises at least three different elements:

- cognitive (thinking) component: an appraisal or judgment

- feeling (subjective) component: what a person experiences privately

- action (or, action tendency) component: either an action or, at least, a tendency to an action

1. Emotions, Autonomic Nervous System Arousal, and the James-Lange Theory

- Emotions arouse the autonomic nervous system – sympathetic ("flight or flight") and parasympathetic ("restoration and relaxation")

- Walter B. Cannon, MD was the first to describe the "flight or fight" response as the body readies itself for a challenge.

So, how can we understand the ways in which the body and the emotions are connected?

Commonsense view:

James-Lange view:

Named for William James (1842-1910; American) & Carl Georg Lange (1834-1900; Danish)

A modern version of this theory says that emotions follow this pattern:

- Event or stimulus which challenges you

- Cognitive appraisal of the situation comes first

- This leads to action (we including our bodies do something; the behavioral- response) and then

- Emotional feeling follows after the action. Hence, an emotion is a kind of thought or conclusion.

A. Is physiological (ANS) arousal necessary for emotional feelings? The results are contradictory

- Evidence AGAINST needing ANS arousal

- People with paraplegia or quadraplegia (paralysis) cannot run away or attack, but feel emotions nearly the same as they did before their paralysis. So, feedback from the motor system (muscles) is not necessary for emotions.

- Damage to right somatosensory cortex leads to normal ANS functions, but little subjective experience in reaction to emotional music.

- Evidence FOR needing ANS arousal

- Pure Autonomic Failure (PAF): A rare condition of middle- and late-adulthood in which ANS output to the body fails, e.g., individual stands up without ANS compensating for the effect of gravity. Such individuals tend to faint. Patients with PAF report having the same emotions, but they experience them as very weak or mild. (Vanderbilt Medical Center, 2023)

- BOTOX (Botulinum toxin) is used for a variety of conditions because it blocks synaptic transmission and nerve-muscle junctions (e.g., muscles on the face which cause frowns). Studies show individuals whose facial muscles are affected by BOTOX report weaker emotions. And, without the ability to frown, people reading unpleasant stories slow down, i.e., they appear to process sad materials slower.

B. Is physiological (ANS) arousal sufficient for emotions? Probably...but only in extreme cases

- Extreme Arousal

- Panic Disorder: Extreme sympathetic system arousal (increased heart rate, increased breathing: similar to experience of suffocating) which is interpreted as fear

- Effects of Facial Expression on Emotion

- Facial Feedback Hypothesis. In a famous 1988 study, researchers reported that individuals who adopt the physical postures associated with some emotions (such as smiling or frowning) report that they experience the same stimuli in different ways, e.g., if forced to smile (clenching a pen in the teeth), people found comic strips funnier than if they are forced to remain closed-mouthed (holding a pen between the lips).

- On the other hand, E.-J. Wagenmakers at the University of Amsterdam and his colleagues (2016) reported that, unexpectedly, attempts to replicate the original 1988 study at 17 different universities with 1,894 participants failed to do so. Wagenmakers et al. (2016) did caution that their findings did not invalidate the facial feedback hypothesis per se either because (1) the experimental design was not strong enough or (2) they may have unwittingly failed to follow a procedure from the original 1988 experiment.

- Because of the Wagenmakers et al. (2016) report, researchers have looked more closely into multiple experiments on the Facial Feedback Hypothesis and how it has been tested. It appears that Wagenmakers et al. (2016) may have slightly altered the procedure of the original 1988 experiment (as they suggested might have happened). A very broad analysis of 138 different experimental studies by Coles, Larsen, & Lench (2019) concludes that "[t[]he available evidence supports the facial feedback hypothesis’ central claim that facial feedback influences emotional experience, although these effects tend to be small and heterogeneous [i.e., variable]" (Abstract, emphasis added)

- Against this notion consider Möbius syndrome (see figure above) ... "primarily affects the 6th and 7th cranial nerves, leaving those with the condition unable to move their faces (they can’t smile, frown, suck, grimace or blink their eyes) and unable to move their eyes laterally" (from Mobius Syndrome Foundation). Nonetheless, these individuals experience happiness and amusement.

Bottom Line: The perception of the body's reactions may be somewhat important for us to interpret our feelings.

C. Is Emotion a Useful Concept?

- Often we do not find that the three elements of emotion (cognition, feeling, & action) actually arise when feeling an emotion.

- As indicated at the beginning, Barrett argues that the classical biological approach to emotion is not true. Emotions are made, not simply uncovered as a reaction to experience.

Limbic System. Barrett (2020) notes that "According to [one] evolutionary story, the human brain ended up with three layers—one for surviving, one for feeling, and one for thinking—an arrangement known as the triune brain. The deepest layer, or lizard brain, which we allegedly inherited from ancient reptiles, is said to house our survival instincts. The middle layer, dubbed the limbic system, supposedly contains ancient parts for emotion that we inherited from prehistoric mammals. The outermost layer, part of the cerebral cortex, is said to be uniquely human and the source of rational thought; it’s known as the neocortex (“new cortex”). One part of your neocortex, called the prefrontal cortex, supposedly regulates your emotional brain and your lizard brain to keep your irrational, animalistic self in check" (pp. 15-16). This triune brain theory was formalized by Paul McLean, MD, a psychiatrist at Johns Hopkins University in the mid-20th century.

- The limbic system consists of forebrain areas bordering the brainstem which includes amygdala, cingulate cortex, hippocampus, fornix, various nuclei (septal, mammillary body), and parts of the thalamus & hypothalamus.

- However, very few studies have reported finding distinctive areas of the brain which correspond to specific emotions. Rather, research with fMRI data shows that multiple areas of the brain -- many more than just the limbic system -- are involved in processing multiple forms of emotion.

- Furthermore, as Barrett (2020) argues strongly, we do not have a "triune brain" at all -- this model, while an immensely popular myth of psychology, has been shown by research in the late 20th and early 21st century to be wrong.

2. Do People Have A Limited Number of Basic Emotions

Paul Ekman (see above) proposed that there are six basic, universal and distinct emotions: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise. His facial expression research showed that people worldwide would correctly identify one of these emotions when presented with a set of posed photographs about 58% of the time.

- Ekman (1999) expanded his listing of basic emotions to others which are not subject to facial display: these include amusement, contempt, contentment, embarrassment, excitement, guilt, pride in achievement, relief, satisfaction, sensory pleasure, and shame.

Other psychologists argue that Ekman's evidence is weak: what about the 42% incorrect responses? Or, people seeing more than one emotion in a single photograph? Or, the reality that we observe more of a person than their face alone?

An alternative approach might be to consider emotional feelings to fall on a continuum as dimensions, e.g., weak vs. strong; approach vs. avoid, etc. A version of this approach was proposed by Jeffrey Gray as noted below.

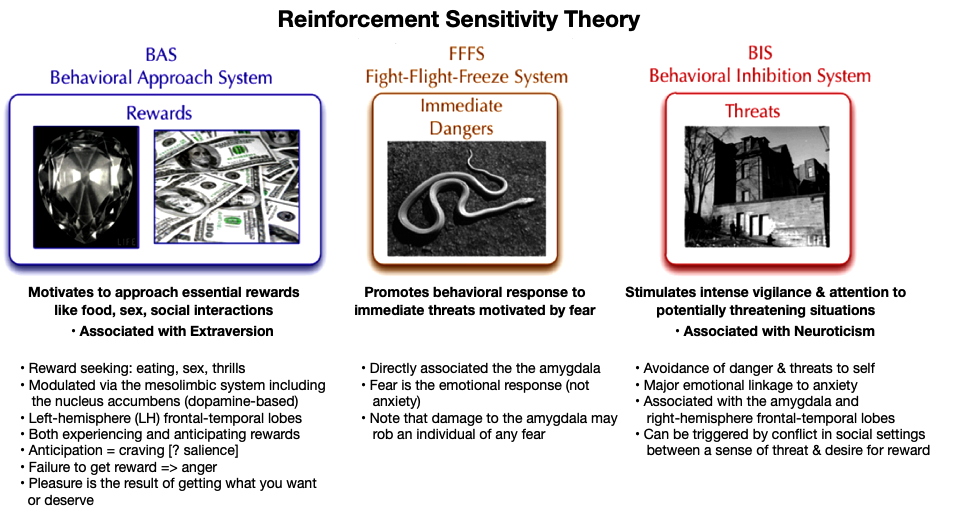

Jeffrey Gray's Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory

Rather than claim a limited number of distinct emotions, the British psychologist, Jeffrey Gray (1934-2004), proposed that the brain has three systems which are particularly sensitive to reward, threat, and punishment and they lie at the root of our experience of emotion. As we grow up and have so many different experiences in the world, these brain systems via classical and operant conditioning are able to very quickly evaluate and respond to the environment. They serve to prompt us toward doing (or not doing!) things.

Behavioral Approach System (BAS): involves (a) the mesolimbic system including the nucleus accumbens [dopamine-based] and (b) the left hemisphere (LH) frontal/temporal lobes and leads to low/moderate arousal of the ANS and a tendency to approach a situation in order to get a reward, i.e., happiness (when rewarded) or anger (when not rewarded).

Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS): involves (a) the amygdala and (b) the right hemisphere (LH) frontal/temporal lobes and leads to inhibition of activity and tendency to fear, anxiety, and disgust.

Fight-Flight-Freeze System (FFFS) is associated with the amygdala and its activation is associated with fear. In the next class, we'll look in more depth at the amygdala, particularly in light of Joseph LeDoux's research. Note that in many animals other than humans, the response to fear is to freeze in place and not move.

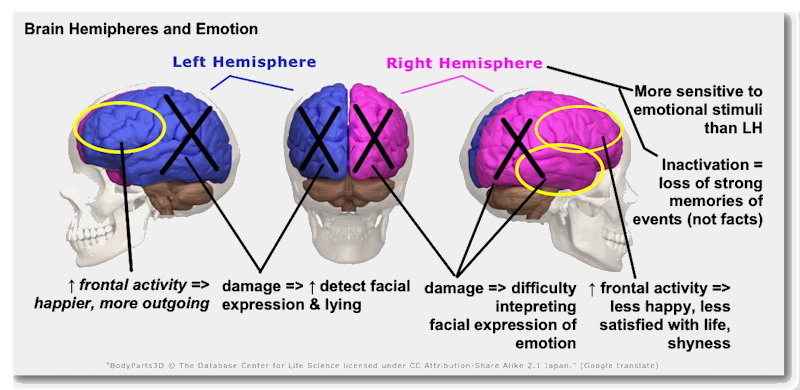

Brain Hemispheres and Emotion

- LH: greater activity in frontal lobe => happier, more outgoing, more fun-loving

- LH damage: Higher than normal ability to interpret facial expression & greater than even chance to detect lying (60% vs. 50%)

- RH: greater activity in frontal lobe => less satisfied with life, less outgoing, prone to negative emotions, shyness

- RH: more sensitive to emotional stimuli than LH

- Right temporal cortex: scanning faces for emotional expression increases activity

- RH damage: Difficulty interpreting facial expression indicating whether a pleasant or unpleasant scene is being viewed.

- RH inactivation (via Wada procedure): facts, not strong emotions, of past events remembered

Positive Emotions: For many years, psychologists focused mostly upon negative emotions like sadness or anger. A major thrust of current research has to do with the nature and number of positive emotions (Shiota et al. 2017). What are these emotions? A listing of those being studied in recent years include amusement, awe, contentment, desire, ecstasy, gratitude, interest, joy, love, pride, relief, sympathy, & triumph (Keltner, 2019). Another proposed grouping by Shiota et al. (2017) suggests a "positive emotion family tree" that links important positive emotions to important reward-system neurotransmitters in the brain (Fig. 4, see below)

Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions of Barbara Fredrickson. One of the major figures in promoting this research has been Barbara Fredrickson who has argued for the last two decades that "positive emotions help us acquire long-term informational, social, and material resources that are important for survival" (Shiota et al., 2017, p. 618, emphasis added). As Fredrickson (2001) proposes in her "Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions," some of the important contributions that these emotions as a group make to human well-being include

- Broadening or increasing the number of potential "thought-action" responses available to people in differing circumstances, These responses flow from greater levels of cognitive flexibility, creativity, and efficiency that appear to come from emotions like joy or contentment.

- Undo the effects of short-term negative emotions which so often leave the body in a state of high arousal (e.g., the cardiovascular [heart/circulation] system returns to more normal levels of activity].

- Fueling psychological resiliency for people who are coping with chronic stress. "Psychological resilience is the ability to cope with a crisis or to return to pre-crisis status quickly. Resilience exists when the person uses "mental processes and behaviors in promoting personal assets and protecting self from the potential negative effects of stressors" (Robertson et al. 2015) In simpler terms, psychological resilience exists in people who develop psychological and behavioral capabilities that allow them to remain calm during crises/chaos and to move on from the incident without long-term negative consequences." {W}

3. The Function of Emotions

A. Moral Decisions and Emotions

You see a runaway trolley car rushing down the tracks and know that the trolley will kill five people walking along the tracks who don't realize it is headed their way. There is a switch in front of you which would immediately divert the trolley to a different set of tracks. However, there is a man walking on those tracks who would be killed if you threw the switch.

What do you do?

From a footbridge above the tracks, you see a runaway trolley car rushing toward five people walking along the tracks who don't realize it is headed their way. They will be killed if the trolley doesn't stop. But, there is a man near you on the bridge. If you push him off the bridge, he will topple onto the tracks, be killed, but stop the trolley. You have to decide whether to push him and save the five people or not push him and watch them die.

What do you do?

Our text also proposed two other scenarios

The Lifeboat Dilemma: If you and 5 other people are in a lifeboat that is beginning to sink, would you consider throwing one person off the lifeboat in order to save yourself and the other 3 people who remain?

The Hospital Dilemma: A surgeon has 5 patients dying because they are missing organ transplants. Each patient needs a different organ. You haven't been able to find any donors. Then, you get word that there is a person visiting the hospital who has the required tissue type needed by each of your 5 patients. Do you kill the hospital visitor to save your 5 patients?

Most people are open to throwing the switch in the Trolley Dilemma and a few are willing to sacrifice the one person in the Footbridge and Lifeboat Dilemmas. But no one would kill the hospital visitor in the Hospital Dilemma.

Although one person is sacrificed in each case in order to save more people, moral decisions based on these examples create strong emotional arousal, especially if it involves actually touching another person to kill them. Indeed, the stronger the level of autonomic arousal, the less likely people are to kill anyone. Hence, we may conclude that decision-making is not purely a "logical" process.

Joshua Green (Harvard University) and his colleagues (2001) found that, when we make decisions, we activate different brain areas if the decision is laden with emotion. The areas associated with increased emotionality (see diagram) include the

- Cingulate gyrus

- Angular gyrus

- Medial frontal gyrus

B. Brain Damage, Emotions, and Decision-makingFor many centuries it was believed that there was an utter separation between rational intellectual decision making on the one hand and irrational emotional responsiveness on the other hand. As Keltner (2019) reflects, "Fifty years ago it was axiomatic to assume that emotions are disruptive forces that undermine higher forms of reason" (p. 3). Then, a large number of research studies examined how reasoning and emotions affect each other. A particularly important area of study was the impact of brain damage on the abilities of individuals to make good decisions. What did this research find?

Individuals with brain damage affecting their emotions make very poor decisions (Antonio Damasio)

Case #1: Man with prefrontal cortex damage

- No emotions felt & he got neither pleasure nor pain from anything

- He knew what the outcomes would be for different actions. But, he could not choose which to do because it was not clear to him whether he preferred a "good" or a "bad" outcome.

Case #2: Young adults who suffered injury to prefrontal cortex in infancy.

- Never learned moral behavior: stole, lied, abused others, etc. No guilt.

- No friends and could not hold jobs.

- Similar to findings of Dr. Dorothy Otnow Lewis among juveniles and adults sentenced to death for murder (Lewis, 1998, 2004). She consistently found histories of significant brain trauma in such convicts.

Keltner (2019) summarizes what psychologists and others have understood about the impact of emotions: "today it is widespread to recognize the wisdom of the emotions, and how they shape thought in deeply rational ways " (p. 3, emphasis added)

References

Barrett, L. F. (2017). The theory of constructed emotion: An active inference account of interoception and categorization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw154

Barrett, L. F. (2020). Seven and a half lessons about the brain. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Beck, J. (2015, Feb. 24). Hard feelings: Science's struggle to define emotions. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/02/hard-feelings-sciences-struggle-to-define-emotions/385711/

Chisholm, N., & Gillett, G. (2005, July 9). The patient's journey: Living with locked-in syndrome. BMJ, 331, 94-97. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7508.94.

Coles, N. A., Larsen, J. T., & Lench, H. C. (2019) A meta-analysis of the facial feedback literature: Effects of facial feedback on emotional experience are small and variable. Psychological Bulletin, 145(6), 610-651. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000194

Ekman, P. (1999) Basic emotions. In T. Dalgleish & T. Power (Eds.), The handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 45-60). New York, NY: John Wiley.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218-226. http://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901309010221

Greene, J. and Haidt, J. (2002) How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(12), 517-523. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(02)02011-9

Greene, J.D., Sommerville, R.B., Nystrom, L.E., Darley, J.M., & Cohen, J.D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral Judgment. Science, Vol. 293, Sept. 14, 2001, 2105-2108. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1062872

Keltner, D. (2019). Toward a consensual taxonomy of emotions, Cognition and Emotion, 39(1), 14-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2019.1574397

Lewis, Dorothy Otnow. (1998). Guilty by reason of insanity: A psychiatrist explores the minds of killers. New York, New York: Ballantine Publishing Group.

Lewis, D. O. et al. (2004). Ethics questions raised by the neuropsychiatric, neuropsychological, educational, developmental, and family characteristics of 18 juveniles awaiting execution in Texas. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 32, 408-29. Available at https://jaapl.org/content/jaapl/32/4/408.full.pdf

Lindquist, K. A., Wager, T. D., Kober, H., Bliss-Moreau, E., Barrett, L. F. (2012). The brain basis of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35, 121-202. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X11000446

Robertson, I. T., Cooper, C. L., Sarkar, M. & Curran, T. (2015). Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12120

Shiota, M. N., Campos, B., … Keltner, D. (2017) Beyond happiness: Building a science of discrete positive emotions. American Psychologist, 72(7), 617-643. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040456

Smith, E., & Delargy, M. (2005, Feb. 19). Locked-in syndrome. BMJ, 330, 406-409. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7488.406

Vanderbilt Medical Center (2023). Pure autonomic failure (PAF). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt Medical Center. Vanderbilt Autonomic Dysfunction Center. Available at https://www.vumc.org/autonomic-dysfunction-center/pure-autonomic-failure

Wagenmakers, E.-J., Beek, T., Dijkhoff, L., Gronau, Q. F., et al. (2016). Registered replication report: Strack, Martin & Stepper (1988). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 917-928. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616674458

Wiens, S. (2005). Interoception in emotional experience [Abstract]. Current Opinion in Neurology, 18(4), 442-447. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wco.0000168079.92106.99

The first version of this page was posted on April 5, 2005.