![[Brain Image]](../graphics/head_space.gif)

PSY 340 Brain and Behavior

Class 02 Introduction: Overview

and Major Issues

|

|

PSY 340 Brain and Behavior Class 02 Introduction: Overview

and Major Issues |

|

The Mind-Body Problem: How are they connected?

What is the relationship between your mind (consciousness, thinking) and your brain (the physical organ)? This is called "the mind-body problem (or "mind-brain" problem).

Consider these two illusions. In both of them we see movement ever though nothing actually moves.

For each of these illusions there is a difference between what is physically present on the screen and what we actually perceive. We are conscious of movement when there is no "real" movement there. Is the reason for this difference that there is something about "the mind" which is special or different than the physical body?

Dualism argues that mind AND body are separate

- Argued by René Descartes (& this view is called Cartesianism)

- Almost ALL philosophers and neuroscientists reject this notion even though it often feels like the right answer.

Monism argues that there is only ONE thing. Most scientists accept monism.

- Materialism: Everything that exists is physical

- Mentalism: Only the mind really exists

- Identity Position: Mind & body are actually the same

- Consciousness is an emergent property of what the body does

- Thus, the mind is an activity of the body (that is, the brain).

Easy vs. Hard Problems (David Chalmers)

- Easy Problems: Describing the different elements of consciousness (sleep vs. awake; orienting in space, etc.)

- Hard Problem: If you are conscious, you are aware of yourself, your history, your future, etc.? How/why is brain activity associated with consciousness? Why did consciousness develop in the first place? If coping with the environment is all about information processing, then why do we need consciousness?

The is a course in biological psychology (also known as psychobiology, physiological psychology, or behavioral neuroscience).

It involves

- Physiology deals with tissues, cells, chemicals, systems of the body

- Evolutionary Psychology deals with genetics and how the earth's physical & social environments have shaped our behaviors for reproductive and survival purposes

- Growth & Development: how does the biology of the body interact with the environment to produce both behavior & structures

Fundamental General Points

- Perception occurs in your brain, NOT on your skin, in your eyes, or somewhere "out there"

- Some people INCORRECTLY believe that we send out some sort of rays from our eyes in order to see the world. This is untrue.

- Be careful about what you claim is an explanation for understanding the brain and behavior, especially if it is based on single scientific studies. Correlation ≠ Causation. For example, if someone is depressed and a scan shows some areas of the brain are less active, this does NOT mean that the lack of activity in those areas is causing the depression.

How Does Biological Psychology Explain How or Why an Animal Looks and Acts Like This?

Let's compare Dogs and Humans once more

- Physiological: How the body as a machine does things: it makes chemicals like hormones, moves the muscles, and causes the animal to act or behave.

- Domestic dogs are the most widely abundant carnivore. Their long association with humans has led dogs to be uniquely attuned to human behavior and they are able to thrive on a starch-rich diet that would be inadequate for other dog-like species. Unlike animals who MUST eat meat, dogs can adapt to a wide-ranging diet, and are not dependent on meat-specific protein nor a very high level of protein in order to fulfill their basic dietary requirements.

- Humans are the dominant omnivorous mammals on the earth. Like all other animals our bodies produce a wide range of chemicals like hormones which regulate (1) our appetites and how much we eat, (2) many of our reproductive behaviors including sexuality, pregnancy, and postpartum nurturing of offspring, and (3) prepare us to face dangers and threats. Though it is not yet completely clear, recent research shows that the composition of bacteria and other organisms in our digestive system (intestines, etc.)–known as our gut microbes or microbiome–has profound effects upon our behaviors and moods, e.g., "alterations in the gut microbiome may play a pathophysiological role in human brain diseases, including autism spectrum disorder, anxiety, depression, and chronic pain" (Mayer et al., 2014, p. 15490). In a couple of weeks I will be saying more about this.

- Ontogenetic (or Developmental): How the behaviors and physical structure actually grow or develop in a specific individual animal. Influenced by and interaction with genetics, nutrition, AND experience.

- In domestic dogs, sexual maturity begins to happen around age six to twelve months for both males and females, although this can be delayed until up to two years old for some large breeds. Dogs bear their litters roughly 58 to 68 days after fertilization, with an average of 63 days, although the length of gestation can vary. An average litter consists of about six puppies, though this number may vary widely based on the breed of dog. The senses of touch and taste are immediately present after birth. The sense of hearing and smell develop, eyes open and the teeth begin to appear 2-4 weeks after birth. Puppies need to begin socializing from 3 to 12 weeks after birth.

- After conception, the gestation period for a human is about 38 weeks (or 266 days). Most women (> 96%) give birth to a single child while the rates of multiple births is about 3.45% (3.35% for twins and 0.10% for triplets or higher order numbers). When humans are born, they require 12 to 14 years to reach sexual maturity. General language development requires about five years from birth to competent speech (we begin learning the sounds of our language in the womb!). Motor development required to move upright on two legs requires 10-12 months. Exposure to visual stimuli in the first five to six years is required for developing binocular vision. Extensive social interaction with the child's caregivers and older humans is required for multiple goals including emotional and social maturity, intelligence, etc. Exposure to toxic substances in the environment during the first five to ten years of life can result in inadequate development of cognitive and other brain functions.

- Evolutionary: How either a structure or a behavior in particular species of animal developed over the course of its evolutionary history. This emphasizes how different animals have similar kinds of structures or behaviors.

- The origin of the domestic dog is not clear. The domestic dog is a member of genus Canis (canines) that forms part of the wolf-like canids, and is the most widely abundant carnivore. The dog was the first domesticated species and appeared more than 15,000 years before present (YBP), with recent studies proposing a divergence time closer to 27,000 YBP. The dog was established across Eurasia before the end of the Late Pleistocene era, well before cultivation and the domestication of other animals around 10,000 YBP, indicating that dogs were domesticated by hunter-gatherers and not early agriculturalists. Dogs show both ancient and modern lineages. The ancient lineages appear most in Asia but least in Europe because the Victorian era development of modern dog breeds used little of the ancient lineages. All dog populations (breed, village, and feral) show some evidence of genetic admixture between modern and ancient dogs. All canids (wolf- or dog-like animals) live in highly social environments; they work together for the sake of the pack. As dogs were domesticated, the highly social behavior continued to be quite prominent, but now included the humans with whom dogs interacted. The behavioral tendency which was lost or softened in dogs (compared to wolves) involves aggressiveness and a tendency to attack.

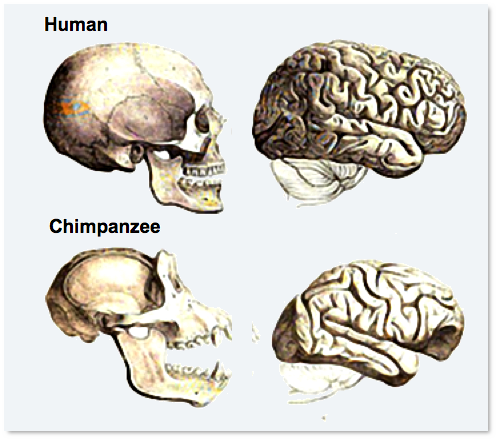

- Humans. Human brains are much larger than most other animals, for example: adult human brains = 1300-1400 g. vs. orangutan = 370 g. vs. gorilla = 465-570 g vs. chimpanzee = 420 g. However, the structure of the brains of all these animals are quite similar. Earlier species of hominins (= human-like animals) mostly showed smaller brain capacities even though the overall shape of the brain was similar across species.

- Notice in the figure above that the basic structure of the brain (e.g., brain stem, cerebellum, and cortex) is the same across each animal. However, in moving from the brain of a rat through to the human brain, the outside cortex not only becomes larger, but also more convoluted, that is, there are many more hills and valleys (gyri and sulci).

- The "Triune" or Reptilian Brain Is A Myth. "The (mistaken) idea that the neocortex [outside, especially frontal part of the brain] was a recent mammalian invention layered on top of older structures gained currency enough to reach the twenty-first century when neuroanatomist Paul MacLean proposed in 1964 his view of a “triune brain,” which consisted of a (1) reptilian complex (from the medulla to the basal ganglia), to which had been added (2) a “paleomammalian complex” (the limbic system), and later (3) a “neomammalian complex”—the neocortex." (Herculano-Houzel, 2016; Kindle locations 507-511).

- We know that birds are descended from earlier reptiles. Given this fact, they should show an "older" kind of brain structure. However, "[t]he brain of mammals is at least as old as the brain of birds and other reptiles, if not older—it just evolved along a different evolutionary path. Indeed, modern neuroanatomical studies showed that the “striatum” of birds has the same organization and function as the cortex of mammals: they are simply two different layouts for a structure that works in very much the same way." (Herculano-Houzel, 2016; Kindle locations 519-523).

- Functional: Why a behavior or a structure evolved or developed as it did. What advantage or benefit comes to us because of the behavior or structure?

- Unlike other domestic species which were primarily selected for production-related traits, dogs were initially selected for their behaviors. In 2016, a study found that there were only 11 fixed genes that showed variation between wolves and dogs. These gene variations were unlikely to have been the result of natural evolution, and indicate selection on both morphology and behavior during dog domestication. These genes have been shown to affect the catecholamine synthesis pathway, with the majority of the genes affecting the fight-or-flight response (i.e. selection for tameness), and emotional processing. Dogs generally show reduced fear and aggression compared to wolves. Some of these genes have been associated with aggression in some dog breeds, indicating their importance in both the initial domestication and then later in breed formation.

- Humans. Around 70,000 YBP, early humans seem to have developed an ability to use language more easily and flexibly than other species of homo, e.g., Neanderthals or Denisovians. This is sometimes called the original "Cognitive Revolution".

- Higher language ability offered two distinctive advantages: (1) planning how to stalk and trap food and (2) learning via gossip and interpersonal talk who to trust and not trust in a group of other humans. Language made larger groups socially possible and this gave humans a distinctive advantage in terms of survival.

(All quotes above describing dogs are taken from Wikipedia entries)

Thus the four explanatory approaches to explain animal behaviors, including human behavior, rests upon physiological, ontogenetic (developmental), evolutionary, and functional points of concern.

Two Important Trends in Contemporary Behavioral Neuroscience (not in book)

1. The "Predictive Brain": The human brain is continually making models of the world around it and updating those models based on moment-by-moment experience (Clark, 2012)

- Rather than start "fresh" every time we enter into a new situation or environment, our brain predicts what it is that it will encounter. That "model" of what we are perceiving is rapidly altered as sensory data either confirms or corrects what the model predicts.

- Most of the modeling takes place outside of direct human consciousness. We are generally unaware of the processes going on.

- Take a look at the "Hollow Face Optical Illusion". As the Wikipedia entry notes, "The Hollow-Face illusion (also known as Hollow-Mask illusion) is an optical illusion in which the perception of a concave mask of a face appears as a normal convex face...According to Richard Gregory (1970) [a very famous experimental psychologist], "The strong visual bias of favouring seeing a hollow mask as a normal convex face is evidence for the power of top-down knowledge for vision." This bias of seeing faces as convex is so strong it counters competing monocular depth cues, such as shading and shadows, and also very considerable unambiguous information from the two eyes signalling stereoscopically that the object is hollow."

Another version of the illusion is seen here:

2. The "Extended Mind" Hypothesis: The mind uses objects external to our bodies by incorporating them into the mind's own functioning. Take a look at this 2011 Doonesbury cartoon about the way in which access to the Internet affects our decision to study something:

The cartoon above was from 2011. Think now about the ways apps and websites are using AI (artificial intelligence) to answer more and more complicated questions.

- For example, if we decide to move something that is out of the physical reach of our arm/hand, we might take up a stick to complete the task. The brain incorporates that stick as if our arm itself grew longer and calculates how the entire arm-hand-stick needs to move in order to accomplish the task.

- Another example: Before we go to bed at night, we might arrange a series of objects on the top of our dresser in a particular order in order to remind ourselves the next day when we get up about something we have to do. The presence of our cell phone before our wallet may alert us that we have to make a specific telephone call (where usually the wallet is located before the cell phone).

- Mary and John are each going to visit the museum. John has early Alzheimer's disease. Mary remembers the directions to the museum and arrives there easily. John has detailed directions to the museum written down in a small notebook, follows those directions, and arrives at the museum. According the "extended mind" hypothesis, the notebook functions as equivalent to the memory processes of the biological brain. (example from Clark & Chalmers, 1998)

Career Opportunities in Biological Psychology

Research

Usually requires Ph.D.Psychological Practice

Usually requires Ph.D. or Psy.D. though some Master's level jobs are possible

Medicine

Requires MD & additional postgraduate study

Allied Medical

Requires Master's degree or higher

Work in universities, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and other research settings

Work in universities & colleges, hospitals, private practice

Work in hospitals, clinics, medical schools, private practice

Work in hospitals, clinics, medical schools, private practice

- Neuroscientist

- Cognitive neuroscientist

- Neuropsychologist

- Neurochemist

- Comparative Psychologist (animal behavior specialist)

- Evolutionary Psychologist

- Clinical Psychologist

- Clinical Neuropsychologist

- Rehabilitation Psychologist

- Health Psychologist

- Counseling Psychologist

- School Psychologist (Master's)

- Neurologist

- Neurosurgeon

- Psychiatrist

- Physician Assistant

- Nurse Practitioner

- Physical Therapist

- Occupational Therapist

- Social Worker

Clark, A. (2012, January 15). Do thrifty brains make better minds? New York Times. Retrieved from http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/15/do-thrifty-brains-make-better-minds

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. J. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58, 7-19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3328150

Eagleman, D. (2015). The brain: The story of you. New York: Pantheon Books. [Kindle ed., loc. 777]

Gregory, R. (1970). The intelligent eye. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2016). The human advantage: A new understanding of how our brain became remarkable. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

Mayer, E. A., Knight, R., Mazmanian, S. K., Cryan, J. F., & Tillisch, K. (2014). Gut microbes and the brain: Paradigm shift in neuroscience. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(46), 15490-15496. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3299-14.2014

This page was first posted January 18, 2005.