Forgetting: When Memory Lapses

![[Hermann Ebbinghaus]](../psy101graphics/ebbinghaus.png) A. How Quickly We Forget:

Ebbinghaus's Forgetting Curve

A. How Quickly We Forget:

Ebbinghaus's Forgetting Curve

- Earliest

studies of forgetting were done by Hermann

Ebbinghaus (1885)

- Used

trigrams = "nonsense" syllables

(consonant-vowel-consonant, e.g., XOR, LIM, WEP,

etc.).

B.

Measures of Forgetting

- Retention = Proportion of

material which is retained or remembered

- Recall: Reproduce information

without any cues

VS

- Recognition: Select

previously learned information from an array of

options

- Relearning: How long does it

take to relearn what you had previously learned?

C. Why We Forget

1. Ineffective Coding

2.

Decay = memory traces fade with age. Not

true except with dementia.

3.

Interference Problem = forgetting

information because of competition from other material

- Retroactive

Interference: New learning interferes with

old learning (NIO)

- Proactive

Interference: Old learning interferes with

new learning (OIN)

4. Retrieval Failure

5. "Motivated" Forgetting

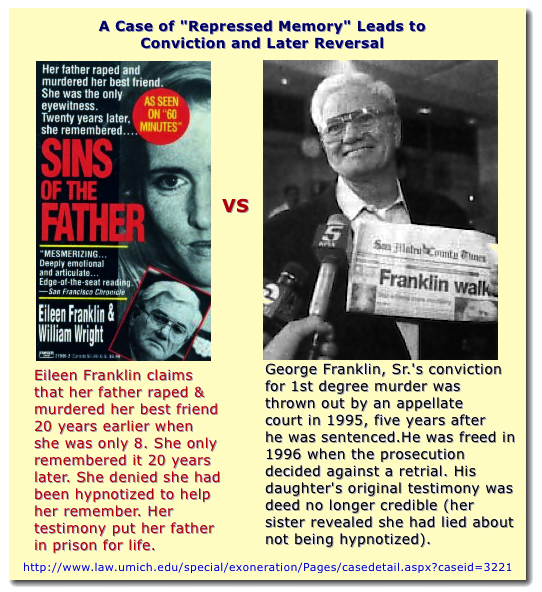

- Sigmund

Freud (1901): Described a process he called "repression"

The Repressed Memory

Controversy

The Repressed Memory

Controversy

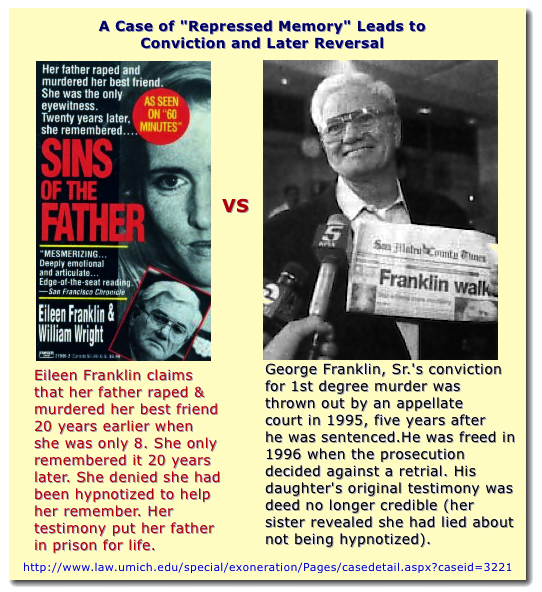

- 1980s-1990s:

Individuals began reporting to their

therapists the recollection of memories, long buried

from the past, which claimed experiences of sexual

abuse, traumas, and even the witnessing of murder. These

memories were considered to be "repressed" as Freud

suggested.

- Elizabeth

Loftus: research showing some false memories can

be implanted

- Estimate

in experimental studies is 30% of subjects will

develop a false memory and 23% accepted that they had

an experience even though they didn't remember it.

- a

memory report can look like a genuine memory to

observers, even if the person does not explicitly

report remembering the events

- PTSD

patients show too many memories

- Bottom

line

- Abuse

is more widespread than we used to think decades

ago.

- "Repressed

memories" are forms of "believed-in imaginings," that

is, even if not factually true, the person reporting

them believes them to be true and are not deliberately

lying

- Therapists

and others (e.g., police) need to be very careful not

to suggest that there are buried memories

The Physiology of Memory

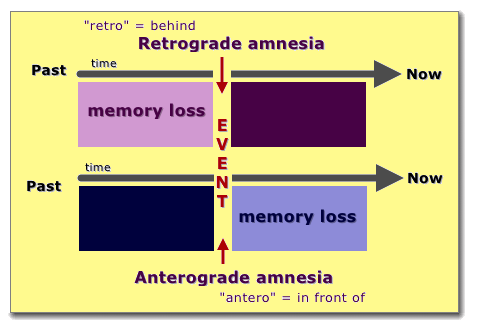

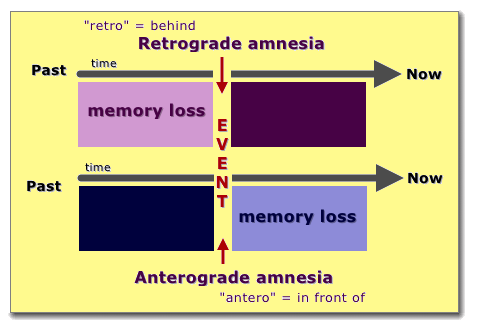

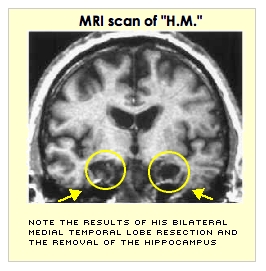

Neuropsychologists

and neurologists have seen for years that there seem

to be at least two different kinds of amnesia, that

is, an inability to remember what happened in the

past, depending upon when some event like a brain

injury took place.

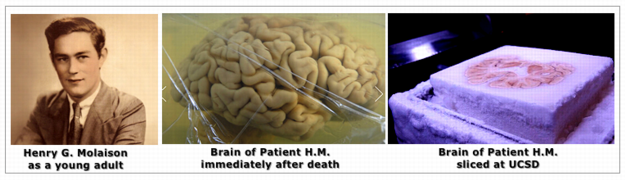

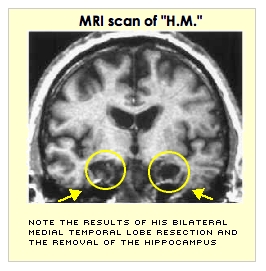

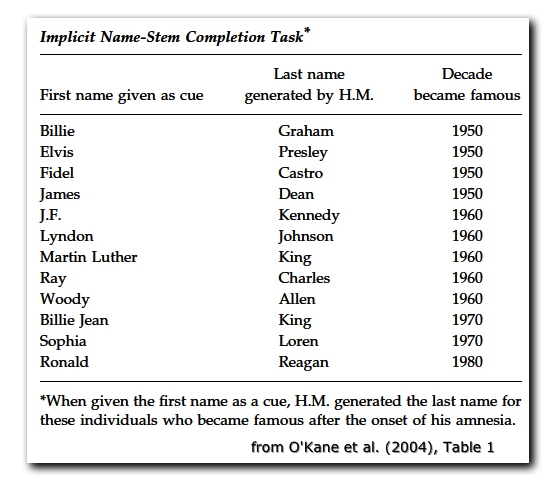

Patient H.M. (Henry Gustav Molaison, 1926-2008)

Here's his story

in a YouTube video [5'25"] from an animated TedEd

presentation.

- Short-term

working memory was fine. He could remember things for 5

to 10 minutes.

- He

could not remember any experience longer than about 5 to

10 minutes, that is, anything that would be a new

addition to his long-term memory. For example, he saw

the same doctors and psychologist day after day, but

never learned who they were.

- He

also had very significant memory loss of events in his

life from before his operation.

- His

overall intelligence remained intact and he could

generally care for himself, carry on conversations, and

enjoy himself with puzzles and other games.

Massive anterograde amnesia = no memory

for any new experiences/learning after operation

Significant retrograde amnesia = very weak memory

for events/experiences from before the operation

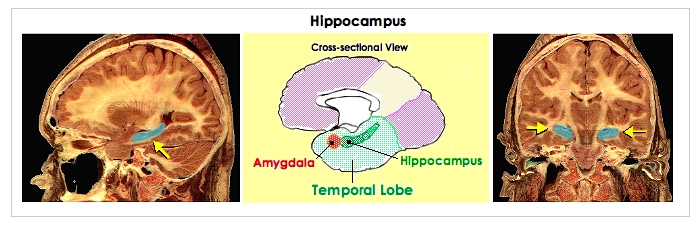

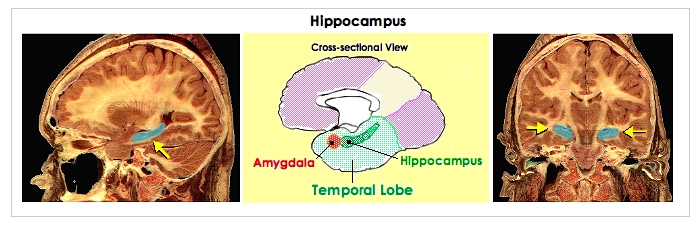

Hippocampus is central to

learning any new explicit or declaratory memory,

but not for implicit or procedural memories (e.g.,

how to do something)

![[Hermann Ebbinghaus]](../psy101graphics/ebbinghaus.png) A. How Quickly We Forget:

Ebbinghaus's Forgetting Curve

A. How Quickly We Forget:

Ebbinghaus's Forgetting Curve The Repressed Memory

Controversy

The Repressed Memory

Controversy